I can't remember the last time I was this angry. I really can't--I'm viscerally, stupidly angry. It's 2:39 am and I'm hot. It's just . . . irrational, maybe. I don't know. It's entirely possible I'm being unfair.

Okay. I just watched

The Artist. For the most part I would say it's a bad film. I respect, in some ways, where the filmmakers are coming from. I appreciate some of the homages to the silent film era and Jean Dujardin isn't bad, he kind of looks like Adolphe Menjou. Berenice Bejo, as the female lead, is just awful--she has that kind of skull face that's popular for women in some circles these days and certainly looks way out of place for a 20s starlet. Yes, thin was in in the twenties, but this lady has a certain legitimised anorexic face that smacks of this young decade. Every still of her face looks like pictures from a shopping mall novelty photo studio.

But that's not why I'm really mad right now. And I can tell I'm past rational, I'm ready to get up and start pacing with rage. The reason I'm so mad, to put it simply, is that

The Artist uses a lengthy portion of Bernard Herrmann's score from

Vertigo.

And I know what you might say. The other part of my brain's already been saying it to me; I've enjoyed movies using scores from other movies plenty of times. I've even enjoyed the use of Bernard Herrmann in

Kill Bill. And it's not like

Re-Animator where Richard Band outright stole music from

Pyscho without crediting it--and even then, I was able to enjoy aspects of

Re-Animator, though what Band did did piss me off (and I don't buy that he intended it as a homage meant to be recognised). But when the piece from

Vertigo started up in

The Artist it was excruciating. The feelings just happened and I have to analyse myself to figure out why. Is it because

Vertigo is holy to me, because I have an extraordinary love for it? Is it just that the action happening onscreen in

The Artist is unworthy of the music? Maybe that's it. Anyway, after getting the nasty surprise while watching the movie, I found out I might have been forewarned if I'd read

the movie's Wikipedia entry;

On 9 January 2012, actress Kim Novak stated that "rape" had been committed in regard to the musical score by Ludovic Bource, which incorporates a portion of Bernard Herrmann's score from Alfred Hitchcock's 1958 film Vertigo (in which Novak had starred). In the article published by Variety she stated that "I feel as if my body - or at least my body of work - has been violated by the movie". "This film should've been able to stand on its own without depending on Bernard Herrmann's score from Alfred Hitchcock's 'Vertigo' to provide more drama," she continued. "It is morally wrong for the artistry of our industry to use and abuse famous pieces of work to gain attention and applause for other than what they were intended," she continued. "Shame on them!I have to say, I am very much with Kim Novak on this. I mean, I don't like to use the word "rape" except when referring to actual rape and I still feel that talking about a misappropriated musical score as rape isn't a good idea . . . but. But I have to say there's something in it. I would definitely call it an assault and a rather intimate one. I don't know, I guess if I wasn't afraid of the word and concept getting trivialised I'd say, yeah. It's a rape.

I remember another time I felt this kind of angry--in a high school art class where I'd come to class one day to find some kid had stabbed holes in the breasts and crotch of a little clay sculpture I'd made of a woman. Part of what made it so hard was the telling myself that I was being stupid, that it was just a little sculpture, not even a good one. The assault coupled with the built in impression that you

have no right to feel the way you do, because it's stupid to feel that way.

Also in the Wikipedia entry is

The Artist director Micel Hazanavicius' response to Kim Novak;

The Artist

was made as a love letter to cinema, and grew out of my (and all of my cast and crew’s) admiration and respect for movies throughout history. It was inspired by the work of Hitchcock, Lang, Ford, Lubitsch, Murnau and Wilder. I love Bernard Herrmann and his music has been used in many different films and I’m very pleased to have it in mine. I respect Kim Novak greatly and I’m sorry to hear she disagrees.And what about that? Let's look at movies I've enjoyed that use music Bernard Herrmann wrote for other movies.

Kill Bill, like nearly all Quentin Tarantino's films, conspicuously uses music from other movies. Even if you don't recognise the music, you're aware of it, either because of sound quality or just because you know it's what Tarantino does. And there's

12 Monkeys, the Terry Gilliam movie that uses parts from the

Vertigo soundtrack, but it's in a movie theatre where the characters are actually watching

Vertigo.

Does making it conspicuous, giving a little knowing wink in the act of using it, make it okay? I guess it does. But maybe more than that,

12 Monkeys and

Kill Bill are good movies and

The Artist isn't. Well, more than that--

12 Monkeys and

Kill Bill aren't saccharine, shallow pieces of shit.

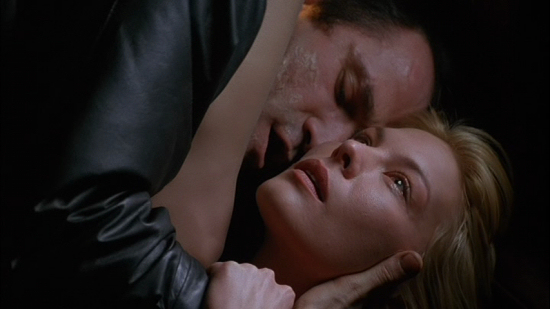

The scene where the

Vertigo music is used is where Dujardin is about to kill himself and Bejo is rushing to the scene to stop him. Why does he want to kill himself? Because he found out that Bejo had been buying his furniture when he'd been auctioning it off after his career as a leading film actor went to pots. Basically he was being a big, huge, baby. Or rather, the movie had to come up with something so we didn't have Happily Ever After at the one hour fifteen minute mark. Never mind most silent films were under an hour.

The central flaw in the movie is

weak fucking characterisation. Particularly as regards the apparent intended main theme of the movie--a man dedicated to his art form. Dujardin plays George Valentin, a silent movie star whose career is jeopardised when movies go to sound. When his studio boss, played by John Goodman, tells him it's over for him and for silent films in general, Valentin quits and goes off to finance a silent film he directs and stars in.

Valentin's story is reminiscent not only, as many have pointed out, of the plot of

Singin' In the Rain, but it has elements of different actual silent actors' lives. The insistence to continue to direct and to finance himself his silent films into the 1930s is reminiscent of Charlie Chaplin, but, of course, Chaplin actually pulled off a successful career at this. A leading lady finding success in talkies helping out her former leading man who's down on his luck because of his unsuitability for talkies is reminiscent of Greta Garbo getting John Gilbert a part in

Queen Christina.

The difference there is that John Gilbert didn't give up the way Valentin did. And Gilbert died miserable without a miraculous lightweight solution like at the end of

The Artist. In any case, Valentin never comes off as a man consumed with getting his art seen by people, just as a guy consumed with getting seen and respected by people. His motives are so pathetically shallow and are taken so seriously it turns the stomach. The movie also lifts scenes from the Douglas Fairbanks

Mark of Zorro and inserts Dejardin's face in the close-ups, though Fairbanks was happily retired by the time talkies came around. More to the point, it emphasises how despite being silent, black and white, and 4:3 aspect ration,

The Artist fails at capturing the timing in terms of editing and composition. You can see too much Spielberg influence in

The Artist's close-ups. And while silent films were often simple hearted,

The Artist is just the wrong kind of simple.