I went to the Marvel trough and fed on the nondescript paste called Avengers: Infinity War yesterday. It wasn't really bad or really good, but felt like an overproduced, late career album from a wealthy rock star. With so many hands in the mix also collectively constrained to strands of continuity, the mandated beats of a modern blockbuster, and the general lifelessness of so much cgi, there's little chance for distinguishable flavour to rise from the soup. But the filmmakers did manage to find a unifying theme.

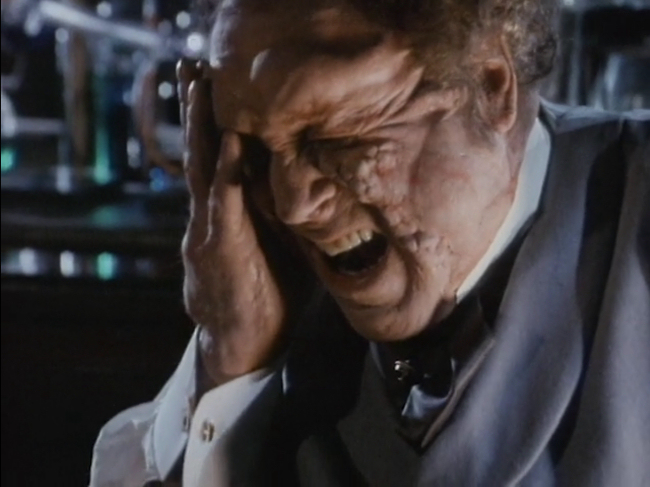

Spoilers after the screenshot

This is a movie about sacrifice. Duh. I suppose there might be two or three people who missed that after it was hammered home again and again and again. Maybe Drax (Dave Bautista) missed it. Not since "With great power comes great responsibility" has a superhero movie so heavily slathered its theme over the top of everything else. One character after another arrives at the point where they must choose between killing another character or allowing disaster to occur.

Let's see if I can remember them all.

Quill (Chris Pratt) has to kill Gamora (Zoe Saldana)--he tries but Thanos (Josh Brolin) prevents it.

Scarlet Witch (Elisabeth Olsen) has to kill Vision (Paul Bettany)--she finally tries but Thanos prevents it.

Loki (Tom Hiddleston) failed to let Thanos kill Thor (Chris Hemsworth) and gave up the Tesseract instead.

Gamora failed to sacrifice Nebula (Karen Gillan), giving up the location to the Soul Stone instead.

Thanos successfully sacrificed Gamora.

Dr. Strange (Benedict Cumberbatch) gave up the Time Stone instead of allowing Tony (Robert Downey Jr.) to die.

This one seems the fishiest, though I don't for a moment believe Loki died trying to stab Thanos with a little dagger. If he really is dead it was the most underwhelming end for any Marvel cinematic character to date.

But Strange giving up the Time Stone for Tony Stark seems really weird. They'd just met--plus there was the earlier scene that abruptly ended when Strange said there was one way out of--I think it was--fourteen thousand they could win. And just before Strange was wiped from existence he said something about how "this was the only way."

I do like that the filmmakers seem to have turned the aspect people complain about most into part of the main idea--the movie's overcrowded and suffers from it; Thanos sees a universe that's overcrowded and suffering for it. So his solution is a seemingly random wiping out of 50% of the population of the universe. Thanos becomes the central figure of the film because of how he factors into everyone else's stories and it's nice that he actually seems conflicted about what he's doing. Josh Brolin delivers a good performance through the veil of cgi, too. So I suppose if one flavour does distinguish itself in this movie it's grape.

The point of all the sacrifices seems to be to ponder the idea over and over--the good of the many outweighs the good of the few but can you put that knowledge in practice if it means killing someone you love?

It's a worthy subject to ponder but diluted a bit in how repetitive it is, and even more by the really really lame wisecracks. Having all these people together did also highlight some of the flaws in the too consistent Marvel formula--suddenly instead of one dopey funny guy and his long suffering, beautiful, and dull girlfriend, we have a hundred dopey funny guys and their long suffering, beautiful, dull girlfriends. There's dopey Quill who won't grow up for Gamora, there's Vision who stumbles over his words while trying to talk to Scarlet Witch, and there was dopey Bruce Banner (Mark Ruffalo) who can't get his Hulk up and his almost girlfriend Black Widow (Scarlett Johansson) who, when a foe is vanquished, quips, "That's rough." To be fair, Black Widow is usually more interesting but, then, most of these characters are. I guess this movie helps you appreciate the circus Joss Whedon ran in the first Avengers.

So the movie ends with a bunch of people dying we know won't remain dead. Unless Spider-Man Homecoming 2 is going to be about Miles Morales. Something that obviously was meant to be a gut punch feels like a waste of time. But the performances were entertaining and some of the comedy from the Guardians of the Galaxy folks was genuinely effective.