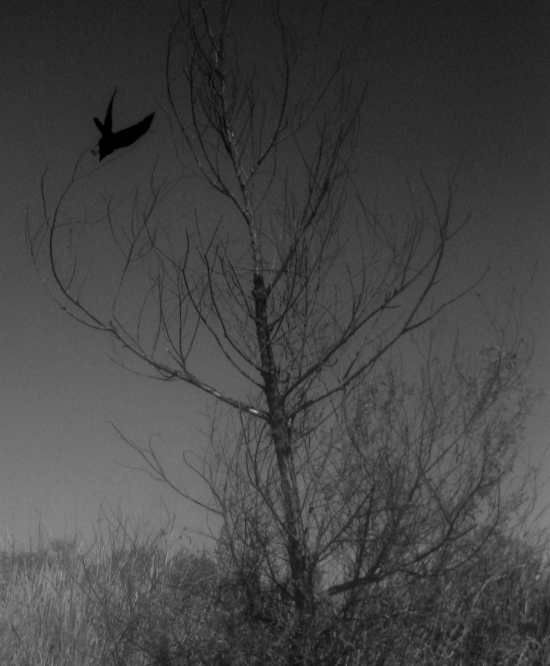

Here's March's;

It was a homage to this scene from The Quiet Man;

August featured Pigeon in Marilyn Monroe's outfit from Clash by Night and in September she wore Sherilyn Fenn's outfit from the Twin Peaks pilot. Which more people would probably get than who got the extremely oblique Twin Peaks reference in the comic itself.

In class to-day, it occurred to me the nature of the epiphany James Joyce sought to portray in "Araby" and "The Dead" was to see darkness as darkness. Throughout both, characters continually impute meanings in both literal darkness and other voids of knowledge; political, cultural, spiritual, and romantic. The most memorable examples, and the two in which the stories are most alike, are in the protagonist's impressions of women he's in love with. Even in "The Dead", when the woman is his wife, Gabriel builds a complex dream around who he thinks his wife is and what she wants but it was really him alone making his impressions the whole time. In both stories, the impetus for the protagonist's mythologising the woman he loves comes when he sees the woman literally half-hidden by darkness; in "The Dead", its when Gabriel sees Gretta standing on the stairs, hearing the music that sparks her reverie that of course he misinterprets at length. Gabriel's epiphany comes when he looks at her and has the strange feeling "as though he and she had never lived together as man and wife." The dissolution of identity, which Joyce likens to an absence that's like an omnipresence of the dead, gives Gabriel the insight of the dark hotel room where the electric light wasn't working and he'd told the porter they didn't need even a candle. "We don't want any light. We have light enough from the street."

Twitter Verses #502: Anne Bradstreet Edition

My meek and horrible dirty word stuff,

Here now mumbles in impertinent guff,

Lines of colossal thighs and great big arms,

Smiting scores while slathering good with balms.

Meagre macaroni would fain conjure

Vulgarities all might justly abjure.

But this rusty teapot reflects a face

More royal than Charles, in bursting grace.

Creation's cabbage, leaves of largess,

His holy head larger than Inverness.

Olympus is a pea beside His tooth;

No cooper compassed His barrel of truth.

Treasure in a billion stone cup of gold.

Oceans of tea, more corn than we can hold.