Here's a movie starring Ingrid Bergman, Fay Wray, and Susan Hayward. 1941's Adam Had Four Sons has a screenplay that's dull as dirt and each of the five males stars, to a man, delivers a performance without the dimmest spark of life. But I have to say the three women actually make this movie worth watching.

The movie begins in 1907 when Adam and Molly Stoddard (Warner Baxter and Fay Wray) are the wealthy parents of four sons. They go to the train station to receive Emilie (Bergman), their new young, French governess.

Bergman's the star of the film and her sensitive reactions convey a genuine affection for the children, a barely repressed, innocent love for Adam once Molly has died, and a wounded quality when confronting Hester, Hayward's character.

Wray's not in the film very long, unfortunately, but long enough to be interesting, injecting elfish mischievousness into a flatly written character.

Hester shows up as the new wife of one of the brothers once they've grown up. She's a home wrecker with never clearly expressed motives unless it's the sexual conquest of every guy in the Stoddard family, which is how she plays it.

Alone and getting drunk in the house with Jack, one of the brothers who isn't her husband, she suggests they go into the city for the day. When he says they're too drunk, she stands up and says, "Well, I guess we'll just have to find something else to do."

They play hopscotch.

That no-one but Emilie has suspicions about Hester is pretty funny in itself. When David, the brother Hester married, brings her home, she greats every man in the family with a full kiss on the lips. She immediately starts calling Adam "Dad" and by the end of the day he's calling her "Darling" and treating her likes she's been in the family for years.

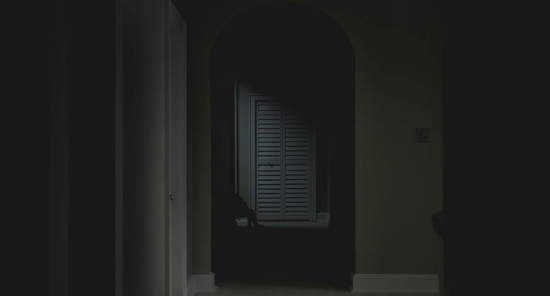

There's an absurd bit of melodrama later where Emilie takes the heat after Adam spies the silhouette of a woman, which was of course was Hester, with Jack in his room. This is how bad screenwriting can lead to rather improbable architecture; first Adam sees the silhouettes because apparently the window of his room is facing the window of Jack's room around four feet away.

When Emilie wakes up to the sound of Adam pounding on Jack's door demanding entrance, she goes all the way around Jack's room where there's another doorway. Hester exits, and Emilie answers the door to Adam, sacrificing the good regard he has for her when he assumes it was her silhouette he saw. Never mind Ingrid Bergman is significantly taller than Susan Hayward.

This plays against the unspoken love Adam and Emilie have for each other. Somehow this guy has lived with Ingrid Bergman for a decade without ever thinking about kissing her. This may be more improbable than the architecture.