I completely forgot what day of the week it was on Wednesday so I didn't get around to watching the season finale of The Expanse until Thursday night. Comprised of two episodes, it certainly was glorious with lots of nice character moments.

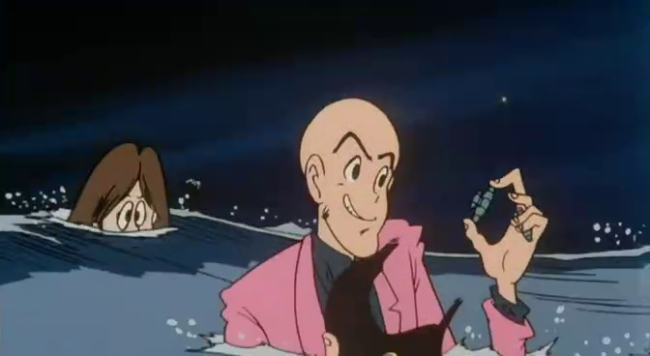

Spoilers after the screenshot

If there was any doubt about Drummer's (Cara Gee) badass credentials, I think they were put to bed when the woman with a crushed spine rigged herself up a new pair of legs just to make sure Ashford (David Straithairn) didn't get out of hand as captain. She was right to be worried though he is a lot more complex than a two dimensional villain.

He has the natural reaction to Holden's (Steven Strait) story--this guy's nuts--but he's open minded enough to remember it when the protomolecule blob reacts to the test bomb. He's smart enough to take in even improbable data, he's experienced enough not to discount anything as impossible. I'm glad Clarissa (Nadine Nicole) didn't succeed in killing him.

Her switching sides was plausible and satisfying. Though it's another moment in her life of looking for cues from other people to decide what she needs to do. At least she listened to the right person this time.

Meanwhile, looks like Amos (Wes Chatham) has found himself a new idol. I've noticed the teleplays have kept Anna (Elizabeth Mitchell) from mentioning her wife to Amos, but, then again, that didn't affect his fixation on Naomi (Dominique Tipper).

Amos had some subtly intriguing development this season. That sort of dead eyed performance Chatham gives actually makes sense now after Amos explained his inability to feel strong emotions a couple episodes back. No wonder he's always looking for a surrogate moral compass. Is he the true "high functioning sociopath" to use the phrase Sherlock made so popular?

Of all the characters, I felt like Anna was the only one really short-changed by the finale. She was wrestling with the fact that she didn't seem to have any compassion for Clarissa so maybe Amos will turn out to be as much a useful model for her as she is for him. Two ships passing in the night. But I miss the line of character development for Anna that seemed to end a couple episodes back. Her mind isn't as much on the meaning of this mission and how her personal life reflects on her involvement in it. Maybe there'll be more of that next season.

The travel rings set up by the protomolecules kind of seem like they're pointing the show in a Deep Space Nine direction--it's like the wormhole to the Gamma quadrant. Now all the factions have to come to some kind of agreement about who gets to use the rings and how and when.

It was a well put together finale, better than last season's, and I look forward to season four.

Twitter Sonnet #1129

The copper hid between the watching stones.

A bristling grass conducts the string aloft.

Abandoned warps observe about the bones.

For wind a battered hatch discreetly coughed.

Computers slip a clicking mortal grip.

A final tick confirms the clock in time.

A portal's fate consumes the match's tip.

An ember holds his pipe in space to climb.

In cactus blurs the questions drop the heat.

Extending suns replace the blue for sky.

The guest became a soft and boiled beet.

The solace of a cape secured the pie.

A late finale moved to early days.

A walking sign creates the newest ways.