The cops look up idly at this strangely positioned murder victim, casually discussing how long it's been since they've dealt with a homocide in their small town. They don't seem especially sorry for the victim or concerned with solving the case beyond going through the motions they're paid to go through. Everyone in the small town depicted in 2009's Mother Ma-deo seems to be generally apathetic or uninterested in their jobs, their community, or even whether or not there's any point to existence. Everyone, that is, except Do-joon's mother, whose tenacity in defending her son against the charge of murder is inexhaustible. And as is usually the case in good films of astonishingly quixotic, focused people, particularly such films from South Korea, Mother is an exceptionally grim film. It's also endlessly inventive and insightful.

Do-joon (Wo Bin), is a young, mentally impaired man who spends his days loitering about town under the intensely watchful eye of his mother (Kim hye-ja) who see early in the film so caught up in watching him she doesn't pay close attention to the shears she's using to cut barley, inching a sheaf through the blades as she cuts and her fingers along with them.

Do-joon's best friend is the charismatic and wealthy Jin-tae (Jin Goo) who immediately chases after an expensive car that hits Do-joon in the street. The two young men track the car to a golf course and Jin-tae instigates a brawl that lands the two young men in the police station.

The lead detective tiredly smooths things over, convincing the golfers that the hit and run and the assault cancel out and that no-one ought to press charges. There's a lazy, sociable village mentality at work one senses has been handed down for generations only to become dulled by distinctly modern apathetic attitudes.

When a golf ball Do-joon had drawn on is found by the murder victim, a young, notoriously promiscuous woman, the police take him in and quickly railroad him into signing a confession.

Another thing that gives one the impression of the film taking place in a small, tight knit community is that Do-joon's mother knows the police detective liked ginseng when he was a little boy to help him remember things he'd studied for a test. Do-joon's mother, who is left unnamed by the film, seems to know all sorts of intimate details about everyone in town from their childhood; she knows the local kids and she gossips with the local women to whom she gives unlicensed acupuncture.

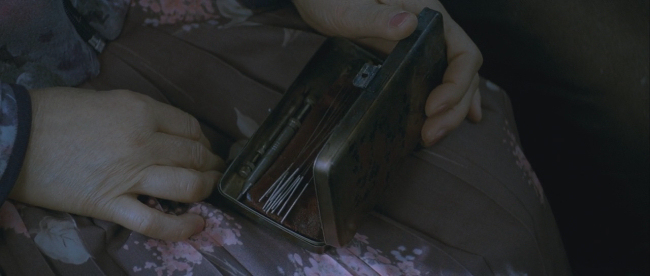

At one point, in a sublimely Hitchcockian/Lynchian scene, Do-joon's mother hides in Jon-tae's closet because she's found a golf club with what looks like blood on the end of it. After watching him and his girlfriend have sex, she slowly sneaks out while they're sleeping, accidentally tipping over a water bottle on the way and we hold our breaths as we watch the water slowly spread across the floor, closer to Jin-tae's finger, threatening to wake him.

Mother was directed by Bong Joon-ho who directed Snowpiercer, a post-apocalyptic film that is nonetheless a lot more cheerful than Mother turns out to be.

South Korea is the grim movie capital of the world. There are all sorts of movies made in South Korea, but the ones that get noticed in other countries--Snowpiercer, Oldboy, A Tale of Two Sisters--are the breathtakingly grim ones. The first South Korean movie I ever saw, 301/302, is a fascinating allegory on the relationship between North and South Korea and that involves self-flagellation and cannibalism.

Mother portrays the one committed person in a world where everyone else has been driven to near catatonia by a brutal sense of meaninglessness. The fact that she's known only as "Mother" throughout the film demonstrates that the sense of purpose in her life is even greater than her individual identity. But then that sense of a meaningless world is confirmed but, like a Werner Herzog hero, the mother's madness enables her to cling tightly to a fervent and extraordinary belief which in turn enables her to take action. The actions she takes may not comply with an external morality the viewer condones but she's motivated by the only morality that matters to anyone, the morality in her own head.