I was going to just talk about Friday to-day but since to-day is the release of the

Twin Peaks blu-ray I figure I ought to talk about Saturday's panel for the release. It wasn't a very exciting panel--it mainly consisted of people who worked on the blu-ray transfer and restoration and they talked about the difficulty they had in finding original negatives for deleted scenes and the Log Lady intros. On that latter note, it was nice to see they

did finally manage to upgrade those introductions, which were originally written and recorded by David Lynch for a Bravo marathon of

Twin Peaks years after the series concluded. In all DVD releases the video is quite muddy, like a VHS transfer. Now it's crystal clear.

The best part of the panel was Kimmy Robertson who played Lucy Moran on the series. She was the only person who originally worked on the series who was on the panel.

The "Unboxing" video she's referring to is this:

The producers of the blu-ray were quite evidently proud of the packaging and made a few disparaging remarks about Netflix and videos streamed through iTunes--they said there has been some HD videos of Twin Peaks available through those services for some time but it is not their restoration, essentially just upsampled from the DVDs. Their work, along with the fabled deleted scenes, is only available through the box set.

My sister was with me on Saturday and sat through two panels with me before the Twin Peaks panel. The panel immediately preceding the Twin Peaks panel was one of the ones where Disney prohibited photography of any kind, a panel called Creative Careers in Entertainment and it featured representatives from Walt Disney Animation Studios, Dreamworks Animation Studios, Cartoon Network, Guillermo Del Toro's Mirada Studios, Blizzard Entertainment, and Jib Jab Brothers Studios.

The representative from Disney, Dawn Rivera-Ernster, moderated the panel, a short, middle aged, soft spoken woman who seemed slightly defensive of an image of absolute peace and love she was endeavouring to pitch to us with a video talking about how Disney animators are a family and community open with one another about sharing ideas. She had begun the panel by telling the room no photos or video recording were allowed and when she concluded the video presentation by smilingly accepting applause for a clip of the "Let It Go" musical sequence from Frozen, she spotted a young man in the front row raising his camera. "No pictures, please," she repeated, looking directly at him but he took a picture anyway, with the flash, to which she could only reply, "Stupid camera guy."

"Oh, sorry," he said.

She laughed and said, "That's okay."

On the one hand, I feel for her because the guy really had done something pretty obnoxious. On the other hand, it was sort of interesting seeing one little crack in the Disney perfect façade she was presenting, just a tiny hint of tension between the image of love for all Disney tries to project and the intensely, feverishly capitalist reality of the Disney corporation.

I'd actually spoken to someone who works in Disney animation earlier that day, an instructor at Walt Disney Studios named Mark McDonnell (this is his web site). He had a booth where he was selling books of sketches he'd done in his free time of monstrous mermaids. I remarked to him that they looked rather Lovecraftian, he nodded and said, "Yeah, I'll take that." So I told him about the priest of Cthulhu using a megaphone to proselytise outside the Con that morning.

Definitely one of the best of the many parodies of the Christian pushers who are always outside the Con, particularly because the language of overpowering doom associated with the Lovecraft mythos is almost indistinguishable from the harsh words coming from the Christians' megaphones. I could tell several people couldn't discern the difference between the Christians and the Cthulhu acolytes. I recalled to McDonnell reading Lovecraft's advice to writers that they read the bible in order to be inspired by the language.

On the Creative Careers panel, Rivera-Ernster, Kim Mackey (Dreamworks), and Brooke Keesling (Cartoon Network), all nodded in agreement when someone observed the importance of drawing inspiration from real life experiences. However, the Mirada Studios representative, Andy Cochrane, an exhausted looking pale young man with dark fatigue circles around his eyes, told the crowd it's helpful to create storyboards from watching television shows and movies, just to get a feel for how the language of film works.

On Friday, I saw a whole panel about storyboards, another Disney panel where video wasn't allowed. However, still photos were, so here's a picture of the subject of the panel, Joe Johnston, director of Captain America: The First Avenger and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids:

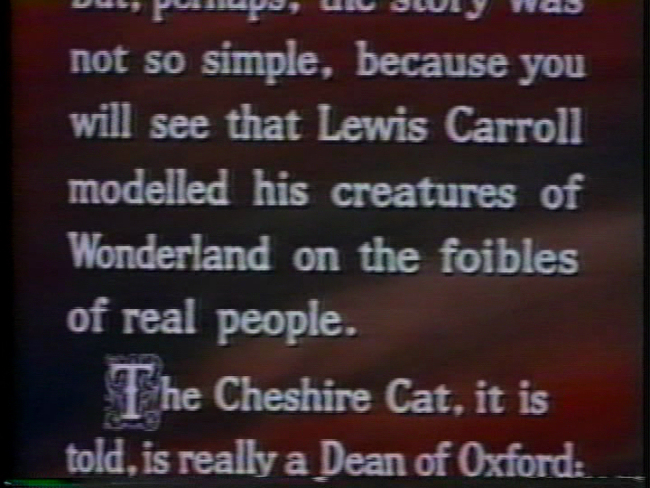

More importantly, he's the former art director at ILM, responsible for a vast portion of the storyboards for the original Star Wars trilogy. The panel mainly consisted of Johnston being interviewed by Lucasfilm editor J.W. Rinzler who introduced Johnston by saying that, after George Lucas, Johnston was the one most responsible for how the original trilogy turned out. Johnston modestly replied Rinzler was given to exaggeration but nonetheless it was clear that Lucas had derived many of his compositions from Johnston's storyboards.

Johnston was also the primary designer of the blockade runner, also known as the Corellian Corvette, and Millennium Falcon. He recalled a story about coming back from lunch to find another art designer had glued on some piece of material to the Falcon model and he'd casually taken out a palette knife and cleanly chipped the thing off, much to the dismay of the other designer.

It sounded like a lot of the work George Lucas did was to come in and draw big red Xs through most of Johnston's storyboards, distilling the collection only to the few Lucas liked. On some days, Johnston said he had produced as many as forty storyboards. Lucas would be very specific about cuts and adds and Johnston described working with Lucas as "Sort of like being in film school."

Johnston described the young George Lucas as a much more hands on director than his reputation suggests now. Lucas would often start shooting scenes without a clear idea of what the scene would ultimately be. He also said Lucas at the time strongly preferred practical effects though, Johnston added glumly, "I don't know if he still does."

When asked about his feelings regarding the cgi Lucas put into the special editions of the films, Johnston said he was fine with them but didn't feel the movies needed them. He did say he was very strongly in favour of J.J. Abrams' return to a greater reliance on practical effects for the new film.

He described an atmosphere of collaboration in the design of the original trilogy and how often he felt no-one could really claim sole credit for a design when the touches of Ralph McQuarrie or Dennis Muren would be there with his. He quoted Muren, the one in charge of special effects for the Star Wars films, as saying it's important to study nature for one's art. This was after Johnston had observed to us that, "The more you experience life, the more you can put in films." He said he'd seen too many films where evidently the makers had only watched television and film.

He talked about how they had a lot of Moebius artwork hanging around the art department, that Lucas and everyone loved Heavy Metal but that it was extremely important to Lucas that everything in the movies looked new.

The panel ended with fans asking questions. When asked whether or not he'd be interested in directing a Boba Fett film, Johnston said he might be, depending on the script. Which sounded like an "Of course" to me.

When asked about the brief period in development when Luke had been female, Johnston said he knew very little about it, that it was at most an idea that lasted three weeks and hadn't involved him.

That's about all I have time for to-day's entry. I'll leave you with this picture of a woman cosplaying as Rosie the Riveter. She told me the jumpsuit had belonged to her father.