What's a bastard to do when cast out upon the world? If it's the title character of 1963's Tom Jones, mostly life is going to involve buxom women and brawling. A mostly faithful adaptation of Henry Fielding's 1749 novel, director Tony Richardson imports some of the energy and postmodernism of the contemporaneous New Wave "kitchen sink" films in Britain to create a new kind of period comedy--its fresh and naturalistic energy enabling it to succeed more in spite of than because of its fourth-wall breaking moments. A lot of credit is due to the incredible cast, particularly Albert Finney in the title role.

The young man who'd credibly evoked working class fury in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning is just as credible here as a fun-loving, devil-may-care gentleman who takes his succession of troubles a little more in stride than the character in Fielding's novel but most of the same plot points remain in tact: A country squire called Allworthy (George Devine) finds an infant in his bed one evening, apparently the cast off of one of the servants, and decides to raise the boy as his own. Tom Jones grows into an amiable young man who likes to sport with Molly (Diane Cilento), the daughter of a neighbour's servant (Wilfrid Lawson). A subtle rivalry develops between Jones and Allworthy's legitimate nephew, Blifil, played by David Warner in his first of a very long line of villainous roles.

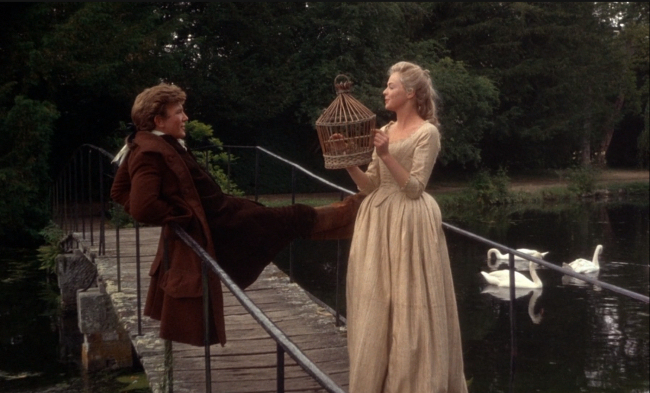

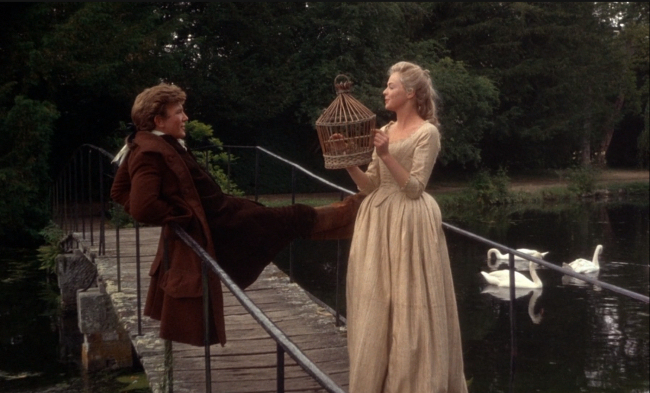

I say subtle because it's primarily all on Blifil's side--Tom hardly seems to notice his cousin's ire, especially after Tom meets the lovely Sophie (Susannah York). Eventually, Blifil's machinations lead to misunderstandings and Allworthy feels compelled to banish the foundling lad, and so begins a series of comedic adventures for Tom. At this point the film elides much of what occurs in the novel and there's less of a sense of Tom's desperation, particularly after he loses the small amount of money Allworthy had given him:

The world, as Milton phrases it, lay all before him; and Jones, no more than Adam, had any man to whom he might resort for comfort or assistance. All his acquaintance were the acquaintance of Mr Allworthy; and he had no reason to expect any countenance from them, as that gentleman had withdrawn his favour from him. Men of great and good characters should indeed be very cautious how they discard their dependents; for the consequence to the unhappy sufferer is being discarded by all others.

One of the most brilliant aspects of the book is how it uses its ingenious plot (one of the best ever contrived, according to Samuel Taylor Coleridge) to show how integral reputation is to a young person's success. I find this a refreshingly common aspect of 18th century writing as it seems as true to-day as it was then but nowadays writers seem more reluctant to discuss the issue. Possibly because writing any story about the importance of influential acquaintance to the advancement of a career might inevitably reflect on such actual acquaintances of the writer.

The idea of Tom being base born is important in the movie as it is in the book, as is the remarkable flexibility in specimens of the upperclass in countenancing society with bastards depending on the bastard's wealth and position. But more focus is placed on the liveliness of Tom's adventures, emphasised by rapid cuts, camera movements, and manic close-ups. The middle section of the novel contains a lovely tour of country inns evocative of Falstaff's Boar's Head but with an illuminating focus on how, even without money, Tom can get by for having the appearance of a gentleman. Fielding also gives a good sense of how reputation is communicated and influential in country public houses, particularly through the indiscreet gossiping of Tom's servant, Partridge.

Here's a character who I wish had a much bigger role in the film, particularly as he's played by Jack MacGowran whose deadpan, easy going delivery perfectly suits the character. This is one of those master/servant relationships I was talking about a couple days ago, a particularly potent example of how it was hardwired into cultural behaviour since Partridge becomes Tom's servant when Tom is penniless, though Partridge doesn't take up with Jones for form's sake alone. Partridge also has a history with Allworthy.

In fact, when Partridge came to ruminate on the relation he had heard from Jones, he could not reconcile to himself that Mr Allworthy should turn his son (for so he most firmly believed him to be) out of doors, for any reason which he had heard assigned. He concluded, therefore, that the whole was a fiction, and that Jones, of whom he had often from his correspondents heard the wildest character, had in reality run away from his father. It came into his head, therefore, that if he could prevail with the young gentleman to return back to his father, he should by that means render a service to Allworthy, which would obliterate all his former anger; nay, indeed, he conceived that very anger was counterfeited, and that Allworthy had sacrificed him to his own reputation. And this suspicion indeed he well accounted for, from the tender behaviour of that excellent man to the foundling child; from his great severity to Partridge, who, knowing himself to be innocent, could not conceive that any other should think him guilty; lastly, from the allowance which he had privately received long after the annuity had been publickly taken from him, and which he looked upon as a kind of smart-money, or rather by way of atonement for injustice; for it is very uncommon, I believe, for men to ascribe the benefactions they receive to pure charity, when they can possibly impute them to any other motive.

But a real affection does develop between Partridge and Jones. You see only a little of it in the movie but Finney and MacGowran have some nice chemistry.

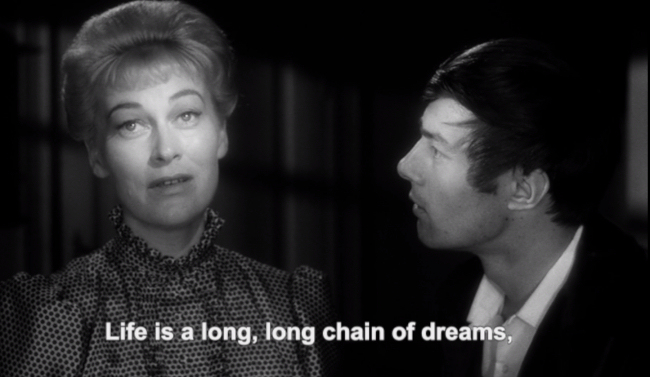

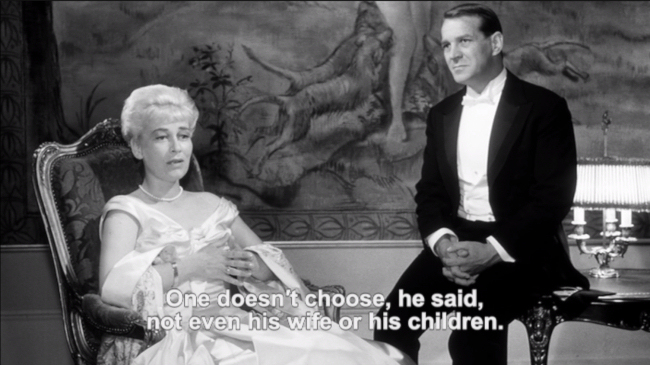

Another thing I was sorry to see diminished in the film is the role of Tom and Blifil's tutors, Thwackum (Peter Bull) and Square (John Moffatt), though, in the interest of keeping the film at around two hours, this is a reasonable thing to trim. Thwackum and Square represent two philosophical forces prevalent in the 18th century, with Thwackum representing tough, Protestant discipline and Square representing new, Atheistic philosophy. Fielding uses the two characters to parody both positions in rendering the two as being almost equally hypocritical and lacking in insight, their arguments often amounting to semantic disagreements entirely useless to Tom's upbringing.

But though [Square] had, as we have said, formed his morals on the Platonic model, yet he perfectly agreed with the opinion of Aristotle, in considering that great man rather in the quality of a philosopher or a speculatist, than as a legislator. This sentiment he carried a great way; indeed, so far, as to regard all virtue as matter of theory only. This, it is true, he never affirmed, as I have heard, to any one; and yet upon the least attention to his conduct, I cannot help thinking it was his real opinion, as it will perfectly reconcile some contradictions which might otherwise appear in his character.

This gentleman and Mr Thwackum scarce ever met without a disputation; for their tenets were indeed diametrically opposite to each other. Square held human nature to be the perfection of all virtue, and that vice was a deviation from our nature, in the same manner as deformity of body is. Thwackum, on the contrary, maintained that the human mind, since the fall, was nothing but a sink of iniquity, till purified and redeemed by grace. In one point only they agreed, which was, in all their discourses on morality never to mention the word goodness. The favourite phrase of the former, was the natural beauty of virtue; that of the latter, was the divine power of grace. The former measured all actions by the unalterable rule of right, and the eternal fitness of things; the latter decided all matters by authority; but in doing this, he always used the scriptures and their commentators, as the lawyer doth his Coke upon Lyttleton, where the comment is of equal authority with the text.

Although Square is the butt of many jokes in the book, I sense, if Fielding had to choose, he'd probably be more on Square's side than Thwackum's. Interestingly, Thwackum is far more developed in the film than Square who comes off as just a quieter version of Thwackum. A few moments of Thwackum shouting about the supremacy of the Church of England establish him in the film as a ridiculous blowhard, and it's not hard to guess where Richardson's opinion lay.

One of the more essential aspects of the book absent from the film is Sophia's struggle to reconcile her love for Jones with the fact that he's constantly sleeping with other women. Sophia in the film is certainly jealous when she learns Jones has been sleeping with Molly and later with Mrs. Waters (Joyce Redman), a woman Jones rescues on the road from a villainous soldier played by Julian Glover (in his first role).

The scene of Sophia leaving the Upton inn upon learning Jones was in bed with Waters omits Jones learning of her discovery and bitterly lamenting it. Also omitted is a curious dialogue between Sophia's travelling companion, Mrs. Fitzpatrick (Rosaline Knight), and herself in which Fitzpatrick talks about loving her husband in spite of the dalliances she knew about. Surprisingly, the film version also changes a moment where Sophia's prejudice regarding the Irish is challenged.

Sophia heaved a deep sigh, and answered, “Indeed, Harriet, I pity you from my soul!——But what could you expect? Why, why, would you marry an Irishman?”

“Upon my word,” replied her cousin, “your censure is unjust. There are, among the Irish, men of as much worth and honour as any among the English: nay, to speak the truth, generosity of spirit is rather more common among them. I have known some examples there, too, of good husbands; and I believe these are not very plenty in England. Ask me, rather, what I could expect when I married a fool; and I will tell you a solemn truth; I did not know him to be so.”

In the film version, Mrs. Fitzpatrick simply exclaims that she should never have married an Irishman. So much for 1960s progressivism. The film also lacks a remarkable observation by Square that Muslims and Jews are just as capable of honourable behaviour as Christians.

Finney is certainly terrific in the role of Jones, notwithstanding a few moments where he looks directly in the camera, and the lively energy Richardson infuses into the film is always engaging. Tom Jones is available on The Criterion Channel.

Twitter Sonnet #1271

A candy shell conducts a choc'late pill.

Compartments flood with flavour crystal blades.

Confection corps ascend the sugar hill.

Platoons of pastries clog the cakey glades.

Evolving raisins drained the seedless grapes.

Contained bananas branched to yellow limbs.

As all the meals were stored on dinner tapes.

As baking worlds involve the furthest rims.

In Skittles bags the weather flukes await.

A timely pudding burbled up a hand.

I mean, a minute hand or hour mate.

As gears and cogs descend in sugar sand.

A can of choc'late flew in kitchen gloom.

A spiral chip design enhanced the room.