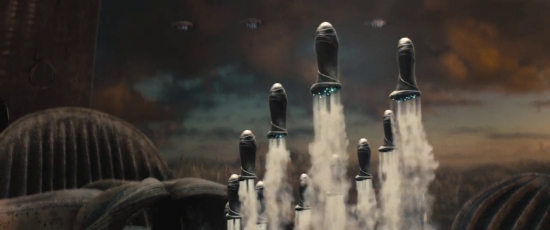

This year Guillermo del Toro, a Mexican filmmaker, made what in many ways is a very American homage to a Japanese film genre. Pacific Rim is a delightful film with brilliant monster battles. Its most ambitious component is in bringing so many aspects distinct to kaiju films and mech anime to a modern, American, live action format than has ever been attempted. But removing that context, Pacific Rim is a far less ambitious film than many of the films or series that influenced it. It feels rather like a child's impression of monster films who has not consciously perceived the subtext. It's a lighter story but certainly quite amazing.

I love how the monsters, created mainly through cgi, have the feel of the men in suits from the old kaiju movies. The filmmakers have banked on the idea that there is a terror inherent in that those monster's movements had an unnatural quality coming from the fact that they didn't have skeletons or muscular systems that quite fit with their exteriors--and it pays off.

The protagonist, Raleigh (Charlie Hunnam), is a distinctly American archetype--a simple, blonde haired, beefy white guy whose psychological issues aren't more complex than missing his dead brother. He's a good, regular joe.

His co-pilot, Mako (Rinko Kikuchi), is closer to a Japanese type of protagonist who is motivated by complex family issues relating to abandonment and self-esteem that have left her deeply scarred. She's one of the aspects of the film that most reminded me of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

And here's where we get to a point I found somewhat distracting. Guillermo del Toro has said in interviews that he's never seen Neon Genesis Evangelion. Of course, the reason he was asked about it is that many people have been suggesting the film draws a great deal of influence from Evangelion. And not unfairly, in my opinion.

In fact, the similarities are so strong that I was able to predict parts of the story based on my familiarity with Evangelion. The giant robots in Evangelion are biomechanical--part organic and part machine--and they have only one pilot. In Pacific Rim, the robots are entirely mechanical and they have two pilots that must mentally synchronise with each other perfectly in order to share the psychological load of being mentally connected to the robots.

When this concept of two people having to mentally synchronise was introduced, I immediately thought, "The male protagonist is going to have to mentally synchronise with a beautiful young woman with whom he is going to have a contentious relationship even as they share a subtle attraction and empathy, just like in the ninth episode of Evangelion."

And indeed, this is what happens when Raleigh and Mako become co-pilots of Gypsy Danger, one of the giant robots.

One can indeed say that story aspects and ideas can arise independently of each other simply because different creative people happened to be writing within the same genre. Yet one can easily put together a paragraph filled with specific story details that apply to both works:

Gendo/Stacker is the stern, brilliant, and self-possessed commander of the organisation which designs, builds, and maintains the giant fighting robots who defend us against giant possibly alien monsters. The organisation is independent but funded by a mysterious council of world leaders to whom Gendo/Stacker must answer in hologram/video conference. Gendo/Stacker is a paternal figure whose aloofness is a difficult thing for his officers to come to terms with. However, he has a mysteriously warm relationship with a young female pilot with short blue hair named Rei/Mako. We learn through Rei/Mako's flashback that Gendo/Stacker had once gone to great lengths to rescue her and in so doing he displayed much more emotion than we're accustomed to seeing him display in the present day.

You see, it's not just the surface details that resemble Evangelion. Mako isn't exactly Rei--she has aspects of Asuka and Shinji as well, especially in that she's driven by a desire to prove herself as an exceptionally capable adult, like Asuka, and she lost her mother under mysterious and monstrous circumstances, like Shinji and Asuka.

But, again, Del Toro says he's never seen Evangelion. I'm inclined to give the benefit of the doubt to the director of Pan's Labyrinth, however derivative I found Hellboy II to be. My suspicion is that Del Toro and screenwriter Travis Beacham reworked a screenplay that had been an attempt to rework Evangelion into an American live action film that was not in danger infringing on any copyrights. And in not being familiar with Evangelion, Beacham and Del Toro unknowingly reworked a reworking into looking more like Evangelion again. Because, after all, if Del Toro didn't want us to know he was drawing inspiration from Evangelion, wouldn't he have consciously made the similarities less pronounced?

And, again, the physics of the monster fights feel much more like kaiju films.

Here's where the film feels especially intriguingly American. The original Godzilla film is very much about the horrors of nuclear power. The film, made in the mid-50s and not long after World War II, is understandably filled with characters who are reluctant to use weapons of mass destruction in view of potential collateral damage to the environment and innocent people. The creature itself emerges from the ocean floor after its lair was inadvertently disturbed by nuclear testing. The implication is that the destruction caused by the beast results partly from our own actions. A beast from the ocean is a nice metaphor for something old and bestial in ourselves being brought out by our new, terrible devices.

In Pacific Rim, although there's a line early in the film about the danger of becoming monsters ourselves, nuclear power is sentimentalised. It's what distinguishes Gipsy Danger's power core--or heart, resembling the sinister S2 engines that power the Evangelions. The other robots in Pacific Rim run on a digital power that is disabled by the monsters. Gipsy Danger's "analogue" nuclear reactor is impervious and more than once it saves the day.

We see buildings and cars destroyed but never the impact on people. There's no horrific collateral damage like there is in Evangelion or in Godzilla. But those works are both from a Japanese perspective while Pacific Rim comes from a place that's never had to deal with the negative effects of nuclear power on such a scale. In the U.S. most people think of the atom bombs has having marked the end of a horrible war.

There's no malice in this perspective in Pacific Rim. Just innocence. And if you take it as a simple hearted, childlike ode to awesome monster fights, it's pretty good.

Del Toro has said about the film, "I don't want people being crushed. I want the joy that I used to get seeing Godzilla toss a tank without having to think there are guys in the tank . . . What I think is you could do nothing but echo the moment you're in. There is a global anxiety about how fragile the status quo is and the safety of citizens, but in my mind—honestly—this film is in another realm. There is no correlation to the real world. There is no fear of a copycat kaiju attack because a kaiju saw it on the news and said, 'I'm going to destroy Seattle.' In my case, I'm picking up a tradition. One that started right after World War II and was a coping mechanism, in a way, for Japan to heal the wounds of that war. And it's integral for a kaiju to rampage in the city."