I liked last night's Game of Thrones, though not as much as "Blackwater", the previous big battle episode directed by Neil Marshall. One thing I really love about the show is how it takes all the glamour out of revenge. I love a good revenge fantasy, I'm a huge Tarantino fan, but I think people too often forget that life is too complicated to facilitate the cleanliness of even Tarantino's typically very thorny paths of revenge.

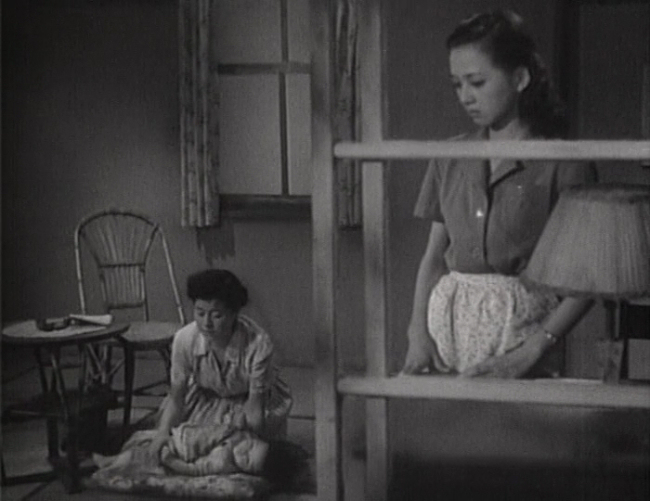

Spoilers after the screenshot

The series has accrued a massive cache of revenge-lust in the heart of Arya and as her desires are routinely thwarted or delayed we see how revenge has gone wrong for other people--most notably Oberyn in "The Mountain and the Viper". In "The Watchers on the Wall", in a bit that diverges from the book, we have a little boy getting revenge for the murder of his father. Now, how could that go wrong? Well, the person he kills is Ygritte, a character we love even after she's killed a bunch of innocent people as well as a few people we actually know and don't hate. Okay, she's a beautiful woman, but really, why should we feel bad if she's killed? For the simple reason that the conflict we see in her is very human. It's easy to watch John Wayne shoot a bunch of guys who are about as complicated as lunch boxes. It's never that simple in life.

The fight choreography was a thousand times better than in the previous episode's duel, very likely due to Marshall's presence behind the camera. And I loved the giants with their mammoths.

Twitter Sonnet #634

Long yellow legs've lifted the walker.

Retracted grain refines the negative.

The sloughing asphalt sparked on the striker.

Imperilled stories drank the adjective.

Dark buoyant office seats bunt the popcorn.

Wan chartreuse bullets button the outline.

Bloodless fears dust the elected lovelorn.

Wax generals transmit the turpentine.

Spades borne by wind briefly touch the dry brick.

Tropical anachronisms won't laugh.

Dust devil walnuts stone the steel woodtick.

Doctor Soda pins blank teeth to the graph.

Premature t-shirts sadden the theme park.

Many myst'ries are known to the aardvark.