Happy New Year and it's time for my annual ranking of the year's movies. It's been a year of contrasts: faith and realism, dreams and cold waking, love and alienation. And it's been a good year for vampires--though I still haven't seen

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night. Maybe it'll be on next year's list. On that note, you may see a few movies on this list you'd consider to be 2013 or even 2012 films. My criterion is availability--if a movie wasn't reasonably available to English speaking audiences until 2014, I included it on this list. That's why

The Wind Rises is on this list, nevermind motherfuckers who managed to see it at a New York festival in 2013. Anyway, everyone's including

The Tale of Princess Kaguya on their 2014 lists and that was released in 2013 in Japan, too.

Without further ado--the list, as always, goes from worst to best:

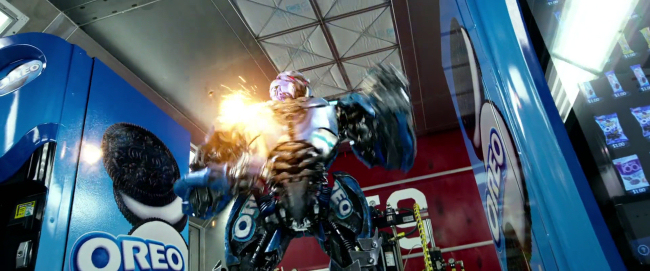

35. Transformers: The Age of Extinction (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

It was a tough call between The Age of Extinction or Gun Woman but, while Gun Woman was misogynistic and sloppily made, at least it felt like the filmmakers actually cared about what they were making. Transformers: The Age of Extinction is noise borne of pure, mindless cynicism.

34. Gun Woman (女イ本銃) (my review, the imdb entry)

A depressing wallow in anger and lust, naked women wordlessly fight or are physically abused by whining, strutting, shitkicking guys. And this makes the women love them.

33. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

The plot is dumb but more solid than Transformers, it's misogynist but not as angry about it as Gun Woman.

32. Dawn of the Planet of the Apes (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Dull human leads detract from some impressive ape performances and everyone is brought down by a textbook plot and silly motivations.

31.Wild (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Good performances by Laura Dern and Reese Witherspoon and some nice scenery couldn't save this movie from its own smugness.

30. Oculus (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Good performances by Katee Sackhoff and Karen Gillen couldn't save this movie from being completely disassociated from its characters.

29. The Edge of To-morrow (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

There's something academic about this movie's mashing of Groundhog Day and War of the Worlds but as a completely by the book spectacle it doesn't actually do anything wrong, its only crime is that it's not in any way exceptional. It deserves a smile at least.

28. The Eternal Zero (永遠の0) (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Fascinating for its peek into the political climate of Japan, this glorifying of Japan's effort in World War II is maybe the first time the nation has so publicly felt pride in its participation in that war. Massively popular in Japan and endorsed by the Prime Minister, it's not likely to see U.S. theatrical release any time soon since it portrays the attack on Pearl Harbour in a positive light. But it's worth noting that the Obama administration didn't order a massive cyberattack on the studio that released it like a certain mutual adversary of Japan and the U.S. might have done.

27. Maleficent (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

This supposedly feminist reinterpretation of Disney's Sleeping Beauty actually manages to be no more feminist than its 1958 predecessor and doesn't make as much sense. But Angelina Jolie looks really good and she clearly had fun in the few moments she gets to portray the classic Maleficent.

26. The Hobbit: Battle of the Five Armies (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

The weakest of Peter Jackson's weaker Middle Earth trilogy, it lacks the visual beauty of the previous instalment and is a lot heavier on the padding. But it has some fun action spectacle.

25. Thorn (가시) (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

It's a little sexist but has two generally interesting characters and one fascinatingly cruel turn of plot.

24. Gone Girl (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

This movie was dumb but slick. It went down easy--it wasn't quite as passionate as the not especially passionate The Edge of To-morrow but even on auto-pilot David Fincher can make a basically entertaining and pretty film.

23. Veronica Mars (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

I'm not sure how well anyone who's not a fan of the show would enjoy this but Kristen Bell's smart, funny, and very human detective always pleases me.

22. Captain America: The Winter Soldier (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

The first wave of Scarlett Johansson's all out assault on the year, this was an entertaining action film with a dash of espionage intrigue far superior to its predecessor.

21. A Winter's Tale (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Nowhere near as bad as its trailer suggests and the critics' manual has instructed people to say it is, A Winter's Tale is gentle and charming for anyone willing to lower their defences.

20. Life Itself (my review: coming soon, the Wikipedia entry)

A somewhat too rosy but still lovely portrait of a great writer whose love of movies elevated the medium for audiences and artists.

19. Giovanni's Island (ジョバンニの島) (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Animation, performances, and dialogue filled with personality but brought down slightly by a run of the mill war refugee story.

18. Boyhood (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

A fascinating portrait on the passage of time painted with a wisely understated brush.

17. Guardians of the Galaxy (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

A good movie if slightly over the top in sentimentality, its success I suspect is largely due more to a thirst for the type of movie it appeared to be--affection not only for Star Wars but I think appreciation for Firefly, Battlestar Galactica, and, more deeply, Farscape, are seeping in the ground soil of the cultural imagination.

16. Interstellar (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Impressive visuals and performances not quite sabotaged by a surprisingly sentimental, somewhat sexist, and generally conservative story.

15. The Interview (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

A much smarter movie than many critics dare give it credit for and funny, too; an amoral jab at the most ridiculous powerful people on Earth--Kim Jong-un and American tabloid media personalities.

14. High Heel (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

A rather bold story of what you might call a noir transgender superheroine. The bigger than life context nonetheless conveys something of the real difficulty transgender people face when transitioning. And it has some great action sequences.

13. The Rover (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Faced with a world that has proven to be fundamentally without any mercy except what luck provides, two men struggle with their need to perceive meaning in the cruelly meaningless desolation.

12. X-Men: Days of Future Past (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

I think a lot of critics have forgotten this movie but it was the strongest comic book movie of the year, maybe the most perfect rendering of the basic drive behind X-Men at its best--youth facing frightening questions about identity and all traditional figures of authority and comfort proving to be just as flawed and downright dangerous.

11. Why Don't You Play In Hell? (地獄でなぜ悪い) (my review: coming soon, the Wikipedia entry)

A vigorous satire of yakuza films and Japan's obsession with nostalgia, this post-modernist gangster movie in the tradition of Branded to Kill was one of the strangest movies of the year.

10. The Grand Budapest Hotel (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Perhaps the most perfect expression of Wes Anderson's aesthetic philosophy and a joy to behold.

9. Snowpiercer (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

An exciting and brilliantly realised Science Fiction film, a microcosm where even the worst potential form of order to the universe is a lie.

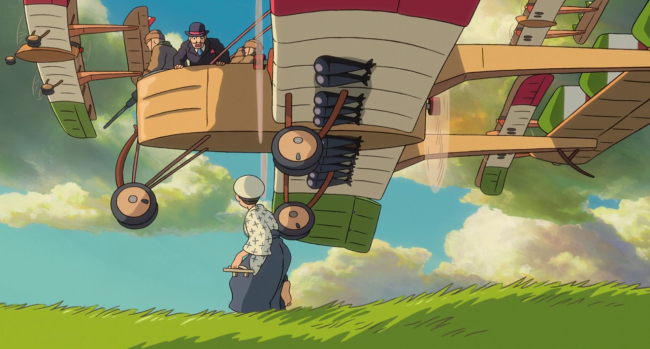

8. The Wind Rises (風立ちぬ) (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Not one of Miyazaki's strongest works, the second half the film is a little bogged down by an uninteresting romance but the fantastic imagery of the protagonist's dreams and a train wreck are still astonishingly wild and beautiful.

7. Only Lovers Left Alive (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

A low key take on vampires by Jim Jarmusch, it's more like an affectionate satire of bohemians.

6. Ida (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Rich in evident influences from the 50s and 60s, this is a gloriously photographed, sombre film about faith in the face of overwhelming revelations of a merciless cosmos.

5. The Zero Theorem (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Terry Gilliam's latest is a return to and an extra riff on the self evident value of imagination in a world that rigorously celebrates universal insignificance.

4. The Babadook (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

An intimate horror film, its terror brilliantly derived from the tenuousness of the critical bond between a widowed mother and her violent young son.

3. Nymphomaniac (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Outside the enforced beliefs of religion, unrestrained self indulgence is contrasted with agnostic asceticism to find the value in each while a curious thread about the divine in life seemingly cannot be repressed.

2. Under the Skin (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

A cool, scary, and melancholy meditation on the instinctive relationship between men and women, on isolation and on the value of empathy.

1. The Tale of Princess Kaguya (かぐや姫の物語) (my review, the Wikipedia entry)

Brilliantly stylised visuals perfectly compliment a story about life and death as veins that permeate all aspects of existence. The organic, the messy, the animal gradually give way to the artificial, the artistic, the dead, and the moon.