Look at those colours and angles. Diane (Laura Dern) is a dragon on that couch.

Last night brought the most linear, logical episode of the new Twin Peaks season so far, but it was still wonderfully weird and refreshing.

Spoilers after the screenshot

Is it just me or did Constance (Jane Adams) and Albert (Miguel Ferrer) just fall for each other over Major Briggs' headless corpse? They seem like they'd be a good couple.

Don S. Davis, who played Major Briggs in the original series--and was forever typecast as a military man afterwards--died some years ago but he's still a big presence on the new series. The sequence of scenes where Bobby (Dana Ashbrook), Frank Truman (Robert Forster), and Hawk (Michael Horse) uncover the capsule that's been kept hidden by Betty Briggs (Charlotte Stewart) all this time was wonderful. Mostly a call back to the surprisingly tender moment from the première of season two between Bobby and the Major at the RR, the scenes in the new episode were both effectively sweet and engrossing as puzzle pieces falling into place.

Sound is playing a very prominent role so far on the new season. This episode features two examples of a strange hum, both in Briggs' capsule and the recurring mystery hum in the Great Northern.

I love these little scenes between Ben Horne (Richard Beymer) and Beverly (Ashley Judd). Beymer's mannerisms as Ben have always been strange and funny and the two actors play out these moments well as little pockets of tension. They're fascinating as a potential affair largely because the sound, Beymer's performance, and the knowledge of Beverly's home life make you wonder what else is going on beneath the surface. Ben Horne was always one of my favourite characters--he was funny, sweet, and scary, and sort of like a dangerous, unpredictable predator. At least until he thought he was Robert E. Lee in season two. I'm glad no-one's dwelling on that.

I wondered if we were going to see Johnny Horne (Eric Rondell) in this season. Apparently that's Ben's wife, Sylvia (Jan D'Arcy) with him though we don't get a good look. It suggests Ben's family life is still as dysfunctional and cold as ever, something where maybe he and Beverly might have a lot in common.

Poor Jerry Horne (David Patrick Kelly) continues his bad trip in the woods. He finds himself in an estranged relationship with his foot, which could be seen as a version of what Ben is going through, though it might also be, like his feeling that his car had been stolen a few episodes earlier, a reflection of Cooper's (Kyle MacLachlan) story, a man whose life is certainly not his own.

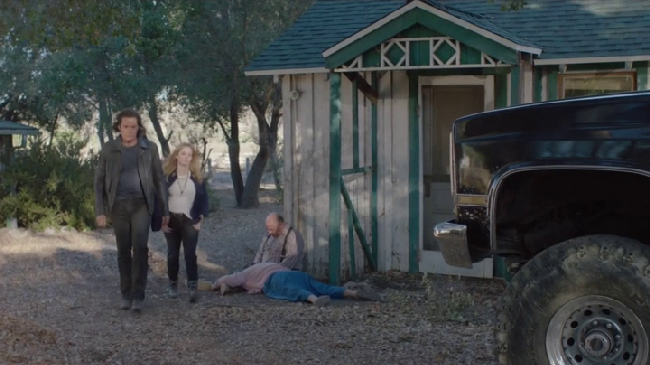

Mr. C arrives at the farm and things feel a bit Tarantino-ish for the presence of Tim Roth and Jennifer Jason Leigh. I hope we'll see more of them both. I love the unexplained pair of people motionless on the ground in the background--such a Lynchian detail.

One of Lynch's talents it's easy to forget about if you watch his movies over and over (like I do) is how good he is at crafting surprises that are strange but also just close enough to credible keep you in the reality. I really, really love the three big cops investigating Dougie's case. I love the one credited as "Smiley" Fusco (Eric Edelstein) whose laugh Lynch deploys with surgical precision. The cops are like classic, cynical noir detectives just tipped into the surreal. Even the sergeant who comes in to take the fingerprints--he's in such a good mood and he's got those weird, big gestures, but it's weird like real people are weird.

I wasn't familiar with Sky Ferrera before this but I loved her scene in the roadhouse where she talks about working fast food places and scratches the huge rash in her armpit. I was reminded of the idea Lynch and Isabella Rossellini had for Rossellini's character in Wild at Heart, that she should somehow be both ugly and beautiful at the same time and that the two qualities should be related to each other in a strange way. Ferrera's conversation with her friend (Karolina Wydra) was also like a deranged version of the conversation between Donna and Maddy in the season two première.

Last night's episode ended with a welcome second performance from Au Revoir Simone. This season of Twin Peaks may end up having one of the greatest soundtracks in the history of television.

If the next Doctor is not a woman, Steven Moffat has done a good job making the people who avoid casting a woman look like massive dicks. That's a little flip but it's true and one of the takeaways from the bittersweet season finale of Doctor Who that aired to-day. If one thinks a bit about the plot, there are a lot of things that don't make sense but the thematic stuff is so good I kind of don't care. "The Doctor Falls" brings a new dimension to the season long focus on mentalities that regard other people as less then human to justify subjugation or murder, the most interesting thread in the episode relating to gender and even gender dysphoria.

Spoilers after the screenshot

If the next Doctor is not a woman, Steven Moffat has done a good job making the people who avoid casting a woman look like massive dicks. That's a little flip but it's true and one of the takeaways from the bittersweet season finale of Doctor Who that aired to-day. If one thinks a bit about the plot, there are a lot of things that don't make sense but the thematic stuff is so good I kind of don't care. "The Doctor Falls" brings a new dimension to the season long focus on mentalities that regard other people as less then human to justify subjugation or murder, the most interesting thread in the episode relating to gender and even gender dysphoria.

Spoilers after the screenshot

I really didn't find John Simm half as annoying as he was under Russell T. Davies, maybe because now he's channelling Delgado and Ainsley so much, but also here he's working as a nice representation of resistance to the idea of a female Doctor along with empathy and femininity in general.

The Master: "Do as she says? Is the future going to be all girl?"

The Doctor: "We can only hope."

This seems a pretty loud and clear way of Moffat saying, yes, the next Doctor ought to be a woman. Moffat also uses Simm's Master to bully Bill (Pearl Mackie) on her gender, the above exchange arising from a subtle reconfiguring of the Cybermen, as a concept, to a socially enforced gender construct. The way Missy (Michelle Gomez) awkwardly apologises to the Master for calling Bill "her" is part of Missy perfectly being placed as the transition point, the people caught in an old fashioned view of gender realising that recognising someone's gender identity is truly more natural than trying to force one on them. Missy really has learned empathy, or gotten back in touch with it.

I really didn't find John Simm half as annoying as he was under Russell T. Davies, maybe because now he's channelling Delgado and Ainsley so much, but also here he's working as a nice representation of resistance to the idea of a female Doctor along with empathy and femininity in general.

The Master: "Do as she says? Is the future going to be all girl?"

The Doctor: "We can only hope."

This seems a pretty loud and clear way of Moffat saying, yes, the next Doctor ought to be a woman. Moffat also uses Simm's Master to bully Bill (Pearl Mackie) on her gender, the above exchange arising from a subtle reconfiguring of the Cybermen, as a concept, to a socially enforced gender construct. The way Missy (Michelle Gomez) awkwardly apologises to the Master for calling Bill "her" is part of Missy perfectly being placed as the transition point, the people caught in an old fashioned view of gender realising that recognising someone's gender identity is truly more natural than trying to force one on them. Missy really has learned empathy, or gotten back in touch with it.

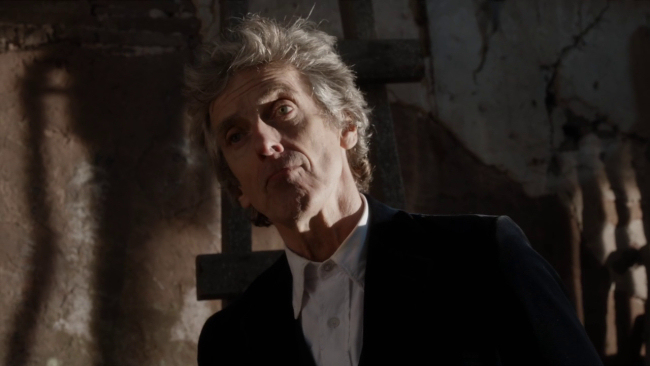

The episode is both about the experience of not being taken as what one sees oneself as and also about the pain involved in change. It's painful for Missy to face that she's not the Master anymore, it's painful for the Master to contemplate his future, and it's painful for the Doctor (Peter Capaldi) to contemplate change again as he begins the process of regeneration.

The episode is both about the experience of not being taken as what one sees oneself as and also about the pain involved in change. It's painful for Missy to face that she's not the Master anymore, it's painful for the Master to contemplate his future, and it's painful for the Doctor (Peter Capaldi) to contemplate change again as he begins the process of regeneration.

Capaldi, it needs hardly be said, is magnificent in this episode, in big and small moments. His discomfort when trying to explain to Bill what's happened to her is so nicely layered with sadness and empathy. This episode actually invokes that word and the Doctor even mentions Donald Trump, making it clear that this season long theme has very much been motivated by the world's current political climate. It leads to a really fitting modification of the Third Doctor's phrase, "Where there's life there's hope" to "Where there's tears there's hope."

Capaldi, it needs hardly be said, is magnificent in this episode, in big and small moments. His discomfort when trying to explain to Bill what's happened to her is so nicely layered with sadness and empathy. This episode actually invokes that word and the Doctor even mentions Donald Trump, making it clear that this season long theme has very much been motivated by the world's current political climate. It leads to a really fitting modification of the Third Doctor's phrase, "Where there's life there's hope" to "Where there's tears there's hope."