If you've ever wondered what it's like for someone from a foreign country to see stereotypes of their nationality portrayed in American films, I think 2000's Brother 2 (Брат 2) might give you a good idea. It's the sequel to the 1997 Russian gangster film Brother (which I reviewed here) but despite having a couple characters in common, the two films are so different I wouldn't say it's necessary to see the first to see the second. It's like if Coming to America were the sequel to First Blood. It's fluff, certainly not half as serious as it takes itself, but enjoyable and sort of sweet.

The super effective killing machine with a perpetual air of innocence and charmingly deficient knowledge of Russian pop culture Danila (Sergey Bodrov Jr.) has relocated to Moscow. He quickly endears himself to Russia's version of Britney Spears, Irina Saltykova (playing herself), when he doesn't recognise her and asks her for directions.

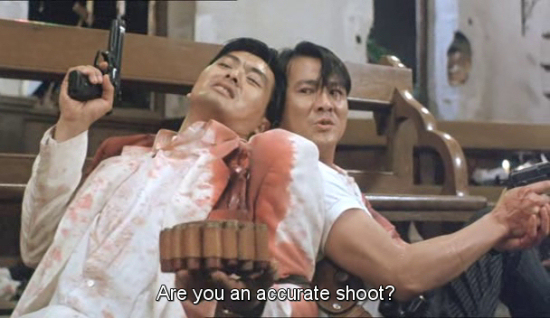

He's on his way to a television appearance with two of his former military comrades, one of whom will shortly afterwards be assassinated in his apartment. The man behind the killing is a bigshot American, so soon it's off to the U.S. for Danila and his brother Viktor for a revenge killing.

This is the same brother from the first film who set Danila up and was part of the film's emotional core about Danila's commitment to his fellow man even when they're not so committed to him. Viktor in this movie is portrayed as a broad, comedic character, practically one of the Three Stooges. In order to evade the heat on them, he and Danila take separate routes to Chicago--Viktor flies straight to Chicago while Danila goes to New York, planning to drive 12 hours to the city in Illinois.

Here Viktor argues with a cop who gets on his case about drinking in public. "Those guys around the corner are doing it!" says Viktor.

"Those guys have their bottles in paper bags!" retorts the cop angrily. They speak in Russian--although Viktor and Danila don't speak English and the language barrier is referred to as a problem for them, they nonetheless seem to run into a lot of people who can speak Russian.

The car Danila buys in New York breaks down on the way and he hitches a ride with an extremely affectionate truck driver stereotype.

They can't speak the same language but they share the universal language of the musical montage as we see them happily getting hotel rooms together, doing their laundry together, laughing together at diners, and poking around at tourist attractions.

When they get to Chicago, Ben (the truck driver) pulls up alongside a row of prostitutes and their pimp who wears a massive fur coat and a gold necklace. This is one of the ways in which the movie has an oddly 70s feel. The American actors sound natural enough but a lot of their dialogue sounds distinctly like it comes from someone who hasn't spent much time in the U.S.

Danila, Viktor, and a Russian prostitute Danila met earlier called Dasha, are amazed that no-one catches the crawfish who crawl right up out of the river. So they're cooking up a big pot of them when Danila refers to a nearby black man as a "negro", prompting a whole group of homeless black men to start a fight with them.

Dasha chastises Danila for not calling the man an African American and Danila complains, "What's the difference?" and says "negro" was the word he was taught to use in school.

The racial stereotypes in this movie are particularly stark, seemingly more as a vague commentary on race relations in America than on the fundamental nature of individuals based on skin colour. When Danila's beaten by the pimp and his friends, he's brought to the police station for questioning. The pimp had told the cops Danila had beaten up Dasha (which he hadn't). The stereotypical fat white cop says, "Fuck the niggers," and lets Danila go.

With the exception of a beautiful television reporter who hits Danila with her car and takes him back to her apartment to have sex with him, everyone black in the movie is portrayed as impoverished and/or criminal.

Viktor says he likes it in America, that money is power and this place was made of money. Danila, when he confronts the man at the top of a skyscraper who he's come to this country to kill, explains money isn't power because it didn't stop Danila from killing him.

Danila's logic isn't airtight, to say the least, but it seems to be the real argument the director's making. Danila and Dasha escape the country in a vintage limousine belonging to Ben, reminding us that for all of America's faults, she has a few perfectly friendly caricatures.

Godspeed, little Russian hitman buddy. Godspeed.