It has great atmosphere and a wonderful story but I think the most remarkable thing about 1996's Arcane Sorcerer (L'arcano incantatore) is that it has stride for its period. I mean, like a samurai whose casual walk tells you he has almost supernatural familiarity with swordplay, Arcane Sorcerer is a period film impressively comfortable with its period. It's as though it was actually made by people from the eighteenth century.

The movie opens with priests interviewing a young man, Giacomo, who, having been coughing up "filth and worms" for days seems to be possessed. We don't see him as he talks to the priests because he's hidden entirely in a shadow. He tells his story to them which forms the bulk of the film, beginning with how he was expelled from seminary school for impregnating a young woman, an upholsterer, and forcing her to have an abortion. How he then sought audience with a witch, who spoke to him from behind a mural with two holes cut into the eyes of an owl.

She arranges for him to become assistant to a defrocked priest who lives in exile in a remote tower. In Giacomo's journey by carriage to the Monsignor's tower he finds himself in the company of two gossiping clergyman, an old woman, and her grand daughter who had just recovered from an illness that had seemed fatal. It's Friday so the old woman begs the indulgence of the clergyman for the anchovies she had prepared in a jar for the journey.

"Of course," says one of the men and she happily distributes some to them before the carriage stops to change horses. All this is done with such solid artistic tread--especially in the last ten years, it's rare for anything "period" to happen in a movie, like eating fish on Friday in a Catholic country, without feeling like a conspicuous announcement. Here, the sight of the fish and the men gobbling them up feels like a natural part of the milieu and incidental stimulus for the kind of story Arcane Sorcerer is.

Giacomo finds the defrocked priest's former assistant, Nerio, has just died under mysterious circumstance, perhaps involving black magic. His wide eyed corpse is wrapped in linen on the kitchen floor when Giacomo arrives and the porter cautions him not to touch any part of the body as they take it out and bury it in a crude grave.

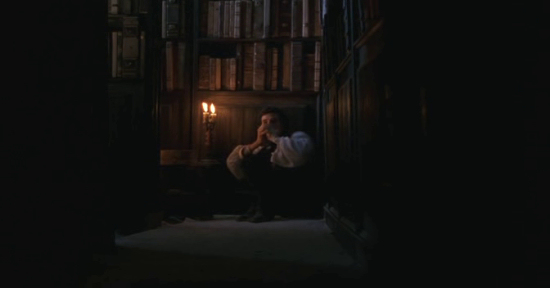

The Monsignor's home is filled with books accumulated over a lifetime and a big part of Giacomo's job is just to comb the shelves for whatever titles his master desires for the evening.

The Monsignor tells Giacomo that the curia misinterpreted his researches into Satanic literature as a genuine interest in the black arts. This mirrors the question of Giacomo's self-worth and fundamentally the movie seems to be a spiritual battle we know from the beginning the protagonist is destined to lose.

The witch, as collateral, asks him to give her the tarot card he keeps sewn into the lining of his cloak, a card which once belonged to his deceased mother. The little girl on the carriage gives him a message from his mother in purgatory and draws a flower on his hand to protect him from the Evil One. Later the Monsignor tells him how throughout his life there have been episodes where he has come across individual Tarot cards, each episode gathering strength to his impression of black magic.

Giacomo certainly doesn't seem a particularly heroic fellow but, like a good noir, one feels dread witnessing his existential downward spiral.

No comments:

Post a Comment