It's terrible when an extraordinary person dies, particularly before his or her old age. Does that mean the death of an average person matters less? Two relatively average teenagers have faced the threat of death all their lives in 2014's The Fault in Our Stars. The title, from Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, subtly subverts the original lines which placed blame on human agency rather than "our stars"--fate or luck, in other words. The two protagonists of The Fault in Our Stars have no one to blame but the gods or luck. This is a good, sometimes rather insightful film.

Hazel Grace (Shailine Wooley) is a beautiful, average teenage girl whose mother and doctor, as the film opens, suspect she has depression because she reads the same book over and over and doesn't have any friends. But Hazel feels this stuff is just a side effect of the fact that she's dying, and has been dying practically all her life. She has cancer that causes her lungs to filled with water, requiring her to carry about an oxygen tank at all times with tubes in her nose.

We never see Hazel's parents, played by Laura Dern and Michael Lancaster, struggling with medical bills and they live in the kind of beautiful home that you usually only see normal families living in in sitcoms, so one can infer they're rather rich, as is Gus (Ansel Elgort), Hazel's boyfriend she eventually meets at a support meeting. We never learn what their parents do for a living or how they got their fortunes. This absence of detail and the lack of other worldly cares that wealth brings isolates the issues Hazel and Gus face related to their mortality and allows them to approach the concept on a purely intellectual, almost theoretical level, except in how it relates to the people around them who will be affected by their deaths.

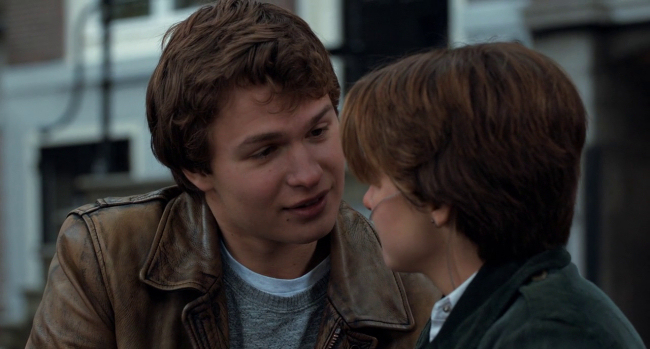

Gus doesn't want to be an average person. He tells Hazel he wants to be remembered though we don't learn of any particular skills or passions Gus has aside from wanting to be famous and loving Hazel. He has a cocky, smarmy exterior and I couldn't help thinking of him as a young Patrick Bateman and wondered whether he might grow up to be a serial killer. Willem Dafoe has a small role in the film as the author of the book Hazel reads over and over and he has Gus and Hazel's number immediately on meeting them--they don't even know how spoiled they are by the amount of affection they receive. So much so that, despite travelling all the way to Amsterdam to meet Dafoe's character, Gus becomes indignant and angry when the man puts on some Swedish hip hop for them, angrily asking if it's a prank, telling the man they don't speak Swedish, not stopping to wonder why this author he admires would play Swedish hip hop for them.

Dafoe's character was my favourite in the film and I found the irony of his two fans completely turning against him when he tries to communicate with them to be absolutely poignant, particularly since, after he's pissed them off, Hazel still finds herself quoting as wisdom something he'd said when he angered them. It's a nice reflection of the fact that, ninety percent of the time, the audience really doesn't know what they want.

And Gus is not an artist. He reminds me of the Morrissey song, "The Girl Least Likely To," about a girl endlessly trying to prove to others she's an artist but is so manifestly incapable of producing art largely because she's incapable of self-reflection. But after all, Gus is a human being, and a very young one, does he deserve to die? What kind of man would he become if he grows out of this youthful arrogance? Cancer robs him of an opportunity that should be everyone's right regardless of talent or wealth, the right to grow and mature.

Although most reviews cite Shailine Wooley's performance as one of the best aspects of the film, we learn very little about her and she functions more as a lens to contemplate Gus. But she has one thread of plot that's interesting where she becomes so obsessed with isolating herself because she doesn't want anyone to be hurt when she dies. Her affections for Gus force her to realise what it's like to be the person who cares, for once, instead of just the one who's cared for.

The film is very cleanly shot and seems slightly to exist in a fantasy world rather than aiming for a hard edged realism, which helps to prevent one from wondering about other aspects of the characters' lives we don't see and wondering why they don't play a part in their contemplations. Although a lot of their dialogue, and shots where they're hanging out with Gus's blind friend, are somewhat reminiscent of John Hughes.

No comments:

Post a Comment