As difficult and strange as cultural change can be, it tends to manifest very close to home, if not in the home, as in the case of Yasujiro Ozu's 1950 film The Munekata Sisters (宗方姉妹). Two sisters, an older and a younger, have different personalities, one shaped more by pre-World War II Japan and the other shaped more by U.S. occupied Japan. Like Kurosawa, Ozu shows in his film that western conceptions of democracy and personal liberty were in many ways healthy new influences on the culture but, while this film isn't quite as eloquent as his better known films, Ozu does succeed in suggesting there are some things lost in such cultural changes because their value cannot be explained in simple logic.

Ozu makes it crystal clear which culture holds sway over which sister. The elder, Setsuko (Kinuyo Tanaka), always wears kimonos and is generally more reserved in her manners while Mariko (Hideko Takamine) always wears western style blouses and skirts. But as with cultural change in general, it's hard to see how much is due to Mariko's youthful rebelliousness and how much is due to Setsuko being set in her ways.

Certainly Mariko seems in many ways still a child. Her father, Ozu's usual face of tranquil wisdom, Chishu Ryu, chides her for her habit of sticking her tongue out.

Mariko's unsure herself if she's behaving properly and needs reassurance, despite her outward assertiveness, and she explains this is why she reads her sister's diary without her permission, to find out if the elder sister was like Mariko when she was her age. And Mariko is surprised to find Setsuko was in love at one time with a young man named Hiroshi (Ken Uehara) but their affair ended when Hiroshi left for France and Setsuko married Mimura (So Yamamura).

We find out that Mimura also read Setsuko's diary and that's why he's out of work and slowly drinking himself to death. Setsuko runs a bar and supports Mimura, just one of the reasons Mariko thinks she should divorce him. When Hiroshi comes back to town, Mariko makes it her personal mission to get Setsuko and Hiroshi back together.

Mariko has no doubts about her quest but it's hard to say how unhappy Setsuko really is since she has that reserved demeanour, seeming perfectly happy to do the household chores for Mimura, though she does stick up for herself when Mimura's drunk and says unreasonable things to her.

At the bottom of the basic philosophical struggle seems to be a conflict between whether it is better to assert oneself to attain happiness and achievements or whether one should take others into consideration and sacrifice for them--and this dichotomy doesn't always match up with the Japanese and Western dichotomy, sometimes one valuing sacrifice more than the other and vice versa. This makes things all the more confusing as Western ideals of sacrifice set off Japanese conceptions of self-denial.

Being young and championing a very firm point of view of right or wrong, however much she might be insecure secretly, Mariko doesn't understand why it's so hard for people to change their lives, why it's so hard for Setsuko to simply get a divorce and reunite with Hiroshi. One character has to explain to Mariko how difficult it must be for the kamikaze pilot who now works at the bar whose life was once about giving everything up for Japan but is now about just being a waiter.

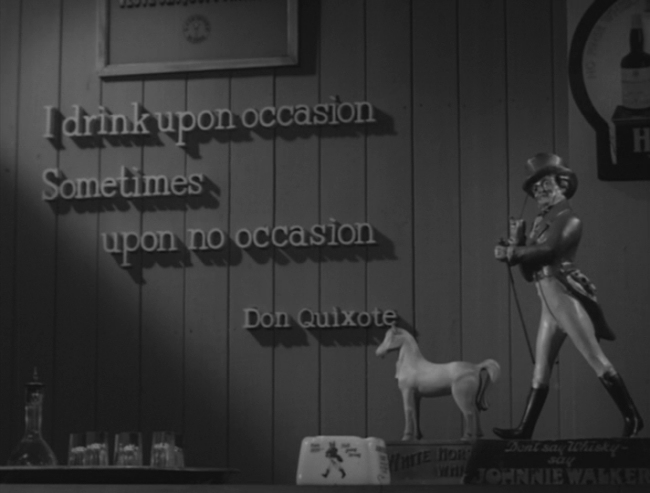

A quote from Don Quixote with a jaunty Johnnie Walker statue at the bar become less and less funny the more they're shown and the more Mimura drinks and this seems a poignant symbol of the unforeseen consequences of dropping aspects of one culture into another.

No comments:

Post a Comment