An adventure film starring Errol Flynn, Claude Rains, and Alan Hale with a score by Erich Wolfgang Korngold can't fail to be good. But 1937's The Prince and the Pauper isn't as good as it could've been, and many of the choices made to adapt Mark Twain's novel are hard to understand. Two of the most emotionally effective moments from the novel are absent from the film and changes are made to characters that are only partly explained by Hays Code morality. But the costumes are magnificent and Rains and Flynn give great performances. Twin boys, Billy and Bobby Mauch, as the title characters, aren't so bad either.

Still, most people probably showed up for Errol Flynn who doesn't appear until halfway through the almost two hour movie. He's perfectly cast as Miles Hendon, the down on his luck gentleman who was deceived by his brother and robbed of his birthright. That whole subplot, a perfect excuse to give Flynn a larger role in the film, is completely removed in favour of a longer build-up to the moment when the two boys fatefully switch places and in favour of spending more time on the machinations of the Earl of Hertford (Rains) who, unlike in the novel, provides an overtly villainous character. It's always a pleasure seeing Rains, though, and he doesn't play him as a man devoted to evil. When the false King asks him for some real advice as Lord Protector, Hertford sits down and lends his ear.

The Captain of the Guard is also built up into a more villainous role, which makes it somewhat perplexing that he's played by Alan Hale. He's written as conflicted, too, and I certainly didn't hate this good natured fellow even as he was ready to stab England's rightful king. This could be an interesting bit of nuance, I suppose.

Hendon's plot is excised in order to spend more time with the boys but the pauper's mother is removed from the story, thereby removing a huge part of his psychological motivation in the last part of the book. Was it deemed too shocking? I'm not sure it really falls under anything forbidden by the Hays Code. There's a longer sequence with Father Andrew (Fritz Leiber) that feels a bit Hays-ish. Certainly the book's allusions to Henry VIII's appropriation of properties formally belonging to the Catholic church present a lot of potential for the Catholic interests behind the Code. Father Andrew, who's already a sad case in the novel, is built up into a saintly figure who consoles the pauper, Tom.

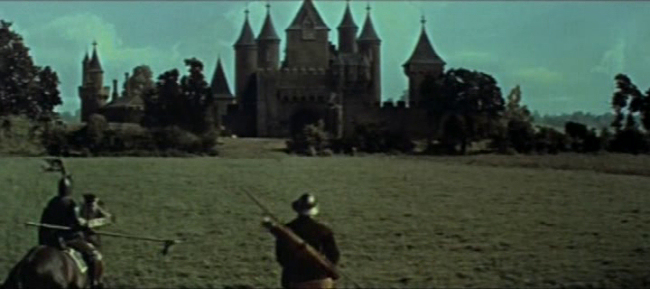

But the sets look fantastic and Flynn looks smashing in costume. More than anything, the film presents a wonderful atmosphere and I'd be happy to roam this 16th century London. It would've been nice if they'd included the wonderful sequence on London Bridge, though. I love the digression with which Twain introduces it;

Our friends threaded their way slowly through the throngs upon the bridge. This structure, which had stood for six hundred years, and had been a noisy and populous thoroughfare all that time, was a curious affair, for a closely packed rank of stores and shops, with family quarters overhead, stretched along both sides of it, from one bank of the river to the other. The Bridge was a sort of town to itself; it had its inn, its beer-houses, its bakeries, its haberdasheries, its food markets, its manufacturing industries, and even its church. It looked upon the two neighbours which it linked together—London and Southwark—as being well enough as suburbs, but not otherwise particularly important. It was a close corporation, so to speak; it was a narrow town, of a single street a fifth of a mile long, its population was but a village population and everybody in it knew all his fellow-townsmen intimately, and had known their fathers and mothers before them—and all their little family affairs into the bargain. It had its aristocracy, of course—its fine old families of butchers, and bakers, and what-not, who had occupied the same old premises for five or six hundred years, and knew the great history of the Bridge from beginning to end, and all its strange legends; and who always talked bridgy talk, and thought bridgy thoughts, and lied in a long, level, direct, substantial bridgy way. It was just the sort of population to be narrow and ignorant and self-conceited. Children were born on the Bridge, were reared there, grew to old age, and finally died without ever having set a foot upon any part of the world but London Bridge alone. Such people would naturally imagine that the mighty and interminable procession which moved through its street night and day, with its confused roar of shouts and cries, its neighings and bellowing and bleatings and its muffled thunder-tramp, was the one great thing in this world, and themselves somehow the proprietors of it. And so they were, in effect—at least they could exhibit it from their windows, and did—for a consideration—whenever a returning king or hero gave it a fleeting splendour, for there was no place like it for affording a long, straight, uninterrupted view of marching columns.

Men born and reared upon the Bridge found life unendurably dull and inane elsewhere. History tells of one of these who left the Bridge at the age of seventy-one and retired to the country. But he could only fret and toss in his bed; he could not go to sleep, the deep stillness was so painful, so awful, so oppressive. When he was worn out with it, at last, he fled back to his old home, a lean and haggard spectre, and fell peacefully to rest and pleasant dreams under the lulling music of the lashing waters and the boom and crash and thunder of London Bridge.

In the times of which we are writing, the Bridge furnished ‘object lessons’ in English history for its children—namely, the livid and decaying heads of renowned men impaled upon iron spikes atop of its gateways. But we digress.