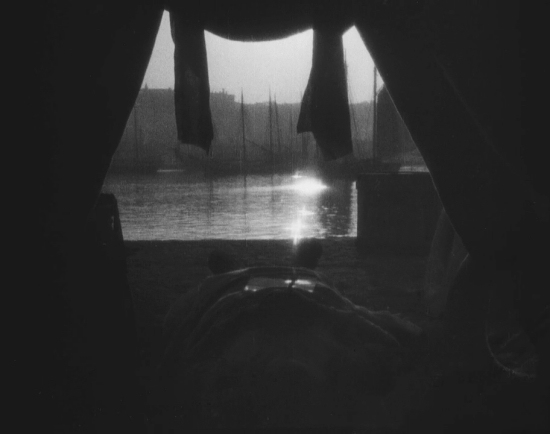

The mind compulsively invests meaning and identity in silence, darkness, or blankness. This begins with, or extends to, the self, a foundation for the crisis explored in Ingmar Bergman's 1966 film Persona. It's a film of ghostly, black and white beauty and an examination of human nature with extraordinary depth featuring performances by two brilliant actresses.

Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann play a nurse, Alma, and an actress, Elisabet, respectively, and the bulk of the movie takes place at a seaside summer home where the two have been sent by the doctor under whom Alma is employed. The purpose is Elisabet's convalescence--the actress having suddenly become silent for several minutes during the performance of a play where she played Elektra before bursting into laughter. Since then, Elisabet, despite having no discernable physical or mental affliction, has entirely refrained from speaking.

Alma expresses to the doctor some trepidation in taking the assignment, as she perceives Elisabet as having a strong personality and herself as delicate and inexperienced, in danger of being overwhelmed by the subject of treatment.

The doctor confronts Elisabet before she sends the two younger women to her summer house, telling the unresponsive actress that she recognises and admires the commitment to her non-participatory role, and encourages her to maintain it as long as it works for her.

Persona is one of those wonderful movies that is very simply itself, contained very precisely in its execution, and yet which can have millions of valid interpretations from viewers. The reason for Elisabet's silence can be interpreted by the viewer as well as by the other characters in the movie. And like the interpretations of those other characters, the viewer's interpretation may say more about the viewer.

In my view, Elisabet's laughter followed by silence indicates an epiphany she's had regarding the nature of personae; she sees them for the meaningless, absurd masks that they are and so she refuses to participate any further and so effects silence. This is the reason, I think, she reacts in horror to footage of a self-immolating Vietnam War protester--the idea of destroying the physical body for a complex set of abstract ideas and beliefs seems monstrous. She's fascinated and horrified by a photograph from the holocaust for the same reason.

In this picture, the only person whose face shows recognition of what's about to happen is the little boy, and it's the boy whom Elisabet focuses on.

It's like a cruel version of "The Emperor's New Clothes". The others may know what's going to happen, but outwardly, and probably on the surface levels of their consciousness, they're not acknowledging it, too caught up in their identities and the reality those identities were crafted to exist in, even though that reality is no longer relevant. Only the kid is able to abandon his ego for truth because his ego is as yet undeveloped and not firmly rooted in his psyche.

The time the two women spend together is initially pleasant. Alma responds to Elisabet's silence as a perpetual demureness, an almost holy humility. Alma is as unguarded with Elisabet as one is with a pet, except Elisabet understands Swedish, and seems to implicitly absolve Alma or forgive her. Alma says she's considered a good listener and has rarely had opportunity to talk about herself before this and seems exhilarated by the circumstance.

She vividly describes to Elisabet an impromptu orgy she took part in on the beach a few years earlier, when a couple boys had found her and her friend Katarina sunbathing nude. In his essay on the film, Roger Ebert says, "The imagery of this monologue is so powerful that I have heard people describe the scene as if they actually saw it in the film." It is extraordinarily vivid and more effectively erotic than any pornography I've seen. Somehow by describing orgasm under the implicitly fictional context of a dramatic movie, Bibi Andersson and the screenplay create a more satisfying rendering than the screaming fits of even the best porn stars. Oddly enough for a piece of cinema, I think this is evidence of the unique power of prose.

But the orgy is at the centre of an existential crisis for Alma. Although she describes the encounter with pleasure reflecting the extraordinary pleasure she must have felt during the experience, it turns to pain as she recounts the abortion she'd had to undergo and the acknowledgement of how the experience of that day had conflicted with her self-conception. Her cries of dismay to Elisabet are deeper than moral shame, although she feels this too. The greater horror she feels is expressed when she asks if beliefs have any reason for being at all. The horror is in the realisation that she could experience pleasure and a sense of self-affirmation by engaging in activities contrary to what her persona dictates ought to give her pleasure. So what is the point of this persona, this collection of ideals?

Driving into town to deliver hers and Elisabet's mail, she opens a letter Elisabet had written to the doctor, and finds in it, in addition to expressions of affection for Alma, also a description of the orgy Alma had confided in her about.

Alma's retaliation is to leave a piece of broken glass on the ground where Elisabet might walk barefoot. When Elisabet indeed wounds herself this way, Bergman cuts to Bibi Andersson coldly watching before looking directly at the camera while scratches appear on the film, as though it's breaking. This neatly conveys an idea of violent, painful tears forming in the intimacy between Alma and Elisabet, at the same time that it conveys the extent of that intimacy. Bergman uses a variety of techniques to convey the idea of the two women merging, often shooting their faces overlapping, concluding at the end of the film with a monologue repeated twice, first showing Elisabet's silent reaction to it, then showing Alma's delivery of it. The monologue is Alma's theory as to the reason for Elisabet's silence, having to do with the shame Elisabet feels about not loving her child. The point in the repetition is to show how each woman exists in the other, the mirror of reaction being a reality. At the end, Alma feels horror because the idea of Elisabet's disgust for motherhood is so contrary to the self-loathing Alma has nurtured regarding her abortion.

Earlier in the film, Alma talks about Elisabet's strength for being an actress, as though Elisabet is bullying Alma in some way through her more sophisticated perspective on personae. Alma's anger is only slackened when she threatens to cast a pot of boiling water at Elisabet, which finally causes Elisabet to speak, to scream, "No, don't!" satisfying Alma that Elisabet can, too, lower herself to self-preservation. The fear is that beneath the clothing of identity there is nothing more than an animal, and the concept of identity is protected with animalistic ferocity.