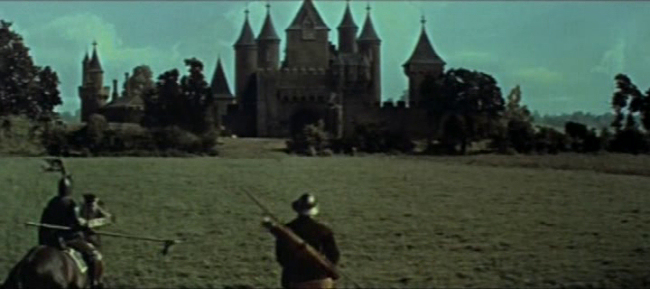

It's a little difficult to describe why I tend to hate Shakespeare productions directed by Jonathan Miller. I generally like Miller in interviews and find myself absorbed by his insight; I love his Alice in Wonderland from the 60s. I even like the adaptations of Shakespeare he produced but didn't direct. But something feels consistently off about the ones he directed for the BBC Television Shakespeare. The impression I often I have is that the actors all rehearsed another play and then transferred wholesale their interpretations to the particular Shakespeare play. A case in point is his 1981 production of Troilus and Cressida, a tragic romance set during the siege of Troy. Shakespeare expands on Homer's descriptions of actions with many conferences among the Greeks, among the Trojans, and between the two, presenting arguments and posturings that at turns reaffirm justifications for policies between the two parties and provide means of psyching one another up for battle. Miller seems like he saw both sides as groups of office workers chatting around a water cooler, an impression confirmed when I read this quote from Wikipedia:

it's ironic, it's farcical, it's satirical: I think it's an entertaining, rather frothily ironic play. It's got a bitter-sweet quality, rather like black chocolate. It has a wonderfully light ironic touch and I think it should be played ironically, not with heavy-handed agonising on the dreadful futility of it all.

I agree there is satire and irony in the play but I think it's a mistake to play it as light.

Hector seems to have the idea:

Though no man lesser fears the Greeks than I,

As far as toucheth my particular,

Yet, dread Priam,

There is no lady of more softer bowels,

More spongy to suck in the sense of fear,

More ready to cry out ‘Who knows what follows?’

Than Hector is. The wound of peace is surety,

Surety secure; but modest doubt is call’d

The beacon of the wise, the tent that searches

To th’ bottom of the worst. Let Helen go.

Since the first sword was drawn about this question,

Every tithe soul ’mongst many thousand dismes

Hath been as dear as Helen—I mean, of ours.

If we have lost so many tenths of ours

To guard a thing not ours, nor worth to us,

Had it our name, the value of one ten,

What merit’s in that reason which denies

The yielding of her up?

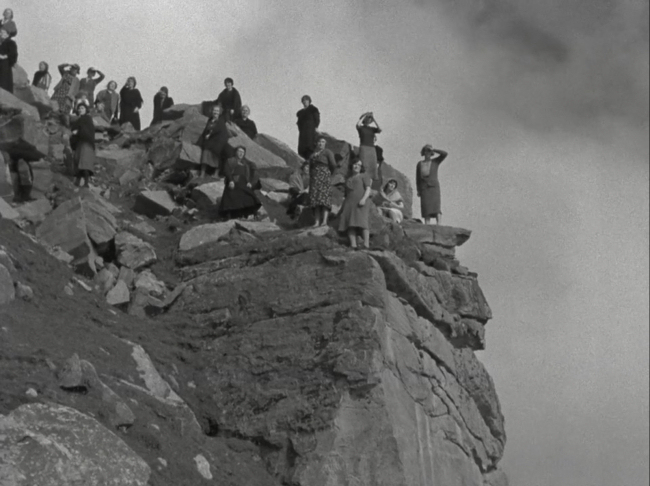

This quarrel over Helen is about to get deadly serious, this point of honour is going to lead to a lot of spilled blood. The chest beating that occurs around this plan to set up a fight between Hector and Achilles has the touch of panic about it, everyone trying to avoid the grim realities that are about to intrude. Miller's Cassandra (Elayne Sharling) interrupts the meeting with a startling screech:

CASSANDRA

Cry, Trojans, cry. Lend me ten thousand eyes,

And I will fill them with prophetic tears.

HECTOR

Peace, sister, peace.

CASSANDRA

Virgins and boys, mid-age and wrinkled eld,

Soft infancy, that nothing canst but cry,

Add to my clamours. Let us pay betimes

A moiety of that mass of moan to come.

Cry, Trojans, cry. Practise your eyes with tears.

Troy must not be, nor goodly Ilion stand;

Our firebrand brother, Paris, burns us all.

Cry, Trojans, cry, A Helen and a woe!

Cry, cry. Troy burns, or else let Helen go.

If Cassandra were so obviously crazy would Troilus (Anton Lesser) have to spend so much time explaining her away?

TROILUS

Why, brother Hector,

We may not think the justness of each act

Such and no other than event doth form it;

Nor once deject the courage of our minds

Because Cassandra’s mad. Her brain-sick raptures

Cannot distaste the goodness of a quarrel

Which hath our several honours all engag’d

To make it gracious. For my private part,

I am no more touch’d than all Priam’s sons;

And Jove forbid there should be done amongst us

Such things as might offend the weakest spleen

To fight for and maintain.

The relationship between Troilus and the young woman Cressida (Suzanne Burden) referenced in the play's title is like an exaggerated reflection of the relationship between Paris (David Firth) and Helen (Ann Pennington) to highlight its faults. In the play's introduction in The Norton Shakespeare, Walter Cohen casually calls the play misogynistic several times though he notes there are productions with feminist interpretations. In Miller's production, Ulysses (Benjamin Whitrow) is presented as a man of wisdom and self possession, which gives more weight to his line, "What hath she done, Prince, that can soil our mothers?" when he hears Troilus railing against all womankind for what Cressida does.

There seems to be a school of thought that if any woman does anything wrong in a work of fiction then it's an indication of the author's misogyny, a generalisation that presents a weird echo of Troilus' about women. Cressida is certainly unusual in Shakespeare--there are other women who do bad things but generally when a woman pledges her love to a man she remains true to her word from beginning to end. There are indications earlier that Cressida may be a little worldlier than Juliet or Ophelia. When Troilus makes to leave their bed after the two have sex, she asks him to stay.

CRESSIDA

Prithee tarry.

You men will never tarry.

O foolish Cressid! I might have still held off,

And then you would have tarried.

Sounds like Troilus might not be her first and, what's more, she's spent some time thinking about how to deal with male psychology. She's not some simple minded young idealist, she's pragmatic, so of course she breaks her word and makes nice with the Greeks when she's in their custody. The strange scene where they all take turns kissing her reminds me of Dracula's brides kissing Harker, a sort of polite, politic variant of assault. Cressida may be trying to mitigate harm but, then again, since her father's chosen the Greek side, maybe she's really getting comfortable with them. Either way, Troilus seems odd for getting so hung up on a woman's sense of honour when her life's on the line.

Actress Suzanne Burden seems as though she was directed to play Cressida just like Juliet and she wails with heartbreak when she's to be separated from Troilus. In her performance there's no sense of the irony or satire or lightness Miller talked about which makes her abrupt switch completely inexplicable. It's as though Miller thought her character was a complete mess and didn't want to bother with her. Certainly she seems committed to Troilus and Troy:

I know no touch of consanguinity,

No kin, no love, no blood, no soul so near me

As the sweet Troilus. O you gods divine,

Make Cressid’s name the very crown of falsehood,

If ever she leave Troilus! Time, force, and death,

Do to this body what extremes you can,

But the strong base and building of my love

Is as the very centre of the earth,

Drawing all things to it. I’ll go in and weep—

But she seems to grow quickly weary of Troilus constantly demanding that she be true when among the Greeks which, if you think about it, as much as she might like to, is a pretty selfish and unreasonable demand on his part.

TROILUS

But ‘Be thou true’ say I to fashion in

My sequent protestation: be thou true,

And I will see thee.

CRESSIDA

O! you shall be expos’d, my lord, to dangers

As infinite as imminent! But I’ll be true.

TROILUS

And I’ll grow friend with danger. Wear this sleeve.

CRESSIDA

And you this glove. When shall I see you?

TROILUS

I will corrupt the Grecian sentinels

To give thee nightly visitation.

But yet be true.

CRESSIDA

O heavens! ‘Be true’ again!

TROILUS

Hear why I speak it, love.

The Grecian youths are full of quality;

They’re loving, well compos’d, with gifts of nature,

Flowing and swelling o’er with arts and exercise.

How novelty may move, and parts with person,

Alas, a kind of godly jealousy,

Which, I beseech you, call a virtuous sin,

Makes me afear’d.

CRESSIDA

O heavens! you love me not!

There are a couple things I like in the production. Charles Gray plays Pandarus as flamboyant and gay, which is a little distracting but kind of fun. Even more fun is The Incredible Orlando as Thersites, a performance that's pitch perfect in its grim cattiness.