I watched L'Avventura last night, Michelangelo Antonioni's 1960 film, widely considered one of the greatest films ever made, though it was booed at its Cannes premiere. It's a reaction I can understand--the movie's about amazingly shallow rich people going on about their lives after the disappearance of someone close to them. In his review of the film, Roger Ebert said of it, "It was seen as the flip side of Fellini's 'La Dolce Vita. ' Both directors were Italian, both depicted their characters in a fruitless search for sensual pleasure, both films ended at dawn with emptiness and soul-sickness. But Fellini's characters, who were middle-class and had lusty appetites, at least were hopeful on their way to despair. For Antonioni's idle and decadent rich people, pleasure is anything that momentarily distracts them from the lethal ennui of their existence."

I was reminded of La Dolce Vita while I watched L'Avventura, but I was even more strongly reminded of The Rules of the Game. All three films tell their stories of decadent societies through series of scenes containing a special kind of vapid dialogue. Love and ambition, or feigned versions of love and ambition, are discussed in collages of casual dialogue at parties, cafes, and other social settings. Over this, in The Rules of the Game, was cast the shadow of World War II. The disappearance of a girl named Anna has a similar effect in L'Avventura.

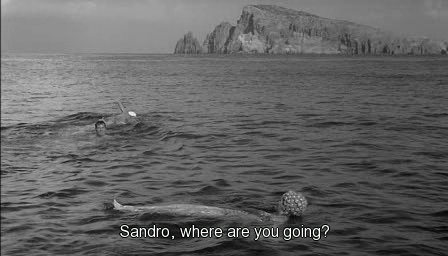

Claudia and Sandro, the film's central characters, were the best friend and lover, respectively, of Anna. The three of them, and several other friends, disembark from their yacht onto an apparently deserted Mediterranean island. Anna had already pretended to spot a shark while they were swimming earlier and laughingly confessed her seemingly pointless prank to Claudia while the two were changing clothes afterwards. Anna is a capricious and bored young woman, complaining to Sandro, from whom she's been separated for a month, that she's become used and prefers to be alone now--right before she has spontaneous sex with him. It's because of this that Sandro initially chalks up Anna's disappearance to one of her games.

But as the characters continue to search the island in a series of beautifully composed, mostly silent shots, analysing Anna's personality takes on a new weight. As the friends struggle between deciding what the flighty and selfish Anna might have done, or what terrible accident may have befallen her, the land and the sea shown in the shots dwarf everything partly because of this tortured confusion. The natural and silent beauty emphasises the small, insubstantial society and the elusiveness not just of Anna but of Anna's personality.

I thought both Claudia and Sandro were pretty crass for engaging in a love affair while Anna's fate was still unknown, but I felt more sympathy for Claudia than for Sandro. Perhaps it's simply because Monica Vitti is an actress who displays emotion a lot better than Gabriele Ferzetti, who played Sandro. The POV shifts between Claudia and Sandro, but it seems mainly to be with Claudia, and while Sandro seems to feel superficial grief for Anna and makes some attempt to investigate her departure, Claudia seems more genuinely wracked with the questions posed by the circumstances about herself and the people around her.

Sandro made me think this movie may work very well as a commentary on modern culture, which seems profoundly impotent. Watching the Zero Punctuation review of the non-existent game Duke Nukem Forever, the sequel to the popular Duke Nukem 3D that's been delayed for nine years, I suspected the reviewer was quite right in his suspicion that the fault lay in game developers slacking off for years. Sandro's an architect and he talks to Claudia about how he'd like to pursue his own designs, complains he lacks opportunity, yet this seems unlikely given his idle lifestyle. At one point he comes across a drawing a young man's made of an antique archway--he casually destroys the drawing without seeming to know why. When the young man confronts him angrily, Sandro asks for his age, which is 23. "I was twenty three once," says Sandro. "I got into many fights."

Of course, I only mean to suggest Sandro's emotionally and imaginatively impotent, as his relationship with Claudia immediately after the disappearance of Anna shows him to be not sexually impotent. He kisses her on the yacht while Anna's still being searched for, and Claudia seems to feel only perplexed alarm before reciprocating. I was sort of working on a theory that Claudia may have been attempting to express a repressed romantic longing for Anna through Sandro, which might explain her participation in the affair. Or perhaps the apparent discomfort she feels on and off may be a pretence she effects for her own sake.

Ultimately the movie seems to be about a guilt over lack of emotions and finally a fear of them.

Twitter Sonnet #178

Skin stolen by shadow shapes moves through day.

Light etches up staircases to a star.

Only lemon marks a landlady's way.

Bourbon sneaks into the Byzantine bar.

Past welcome words walk from the tongue's tunnel.

Ninja whittler cheats at origami.

Cardboard beast's driven into a kennel.

Smeagol has stolen all the sashimi.

Goblins watch the scientific sunrise.

Teeth ping pong in petrified pantyhose.

Raised liver spots on rocks dream they're dead flies.

See where a ketchup covered florist goes.

White rock ramparts see a funeral veil.

Rust marches among rings of iron mail.

No comments:

Post a Comment