Although it ostensibly seems to be about hypnotism, Kiyoshi Kurosawa's 1997 film Cure uses the device of fictional hypnotic techniques to tell a story about the power of messages and the human capacity to control the perceptions of others. It's an interesting film, flawed but cunningly shot and with extremely thoughtful and thought provoking dialogue.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa is of no relation to Akira Kurosawa nor does his filmmaking style seem to be influenced by the more well known Kurosawa. Wikipedia quotes him as listing Hitchcock and Ozu as influences. I can certainly see Hitchcock, though it's hard to see how Ozu had any particular influence on such a tense, bloody film. Released in 1997, it's right at the beginning of the era in Japanese media heavily influenced by Neon Genesis Evangelion, and Kiyoshi Kurosawa's use of train signals for transition shots as well as the psychological quality of the movie are both reminiscent of Hideaki Anno's series.

I've never wanted so badly to see a cop go Dirty Harry on a suspect. Mamiya, the film's antagonist, is an irritating little jerkoff who abuses his ability to make people kill each other like a kid casually wrecking the Porsche his daddy bought him. His technique is to approach his victims feigning amnesia, thereby conning them into telling him all about themselves while he reveals little about himself. In this way he subtly tweaks their perceptions until he makes killing someone seem natural. He uses hypnosis to insert his commands into the chains of motivations he draws out of them.

The really nice thing about this film is how Kiyoshi Kurosawa's technique evokes a sense of the thought process in a way that's difficult to describe.

In my favourite scene, the protagonist, Detective Takabe, tracks down Mamiya's residence while Mamiya's in custody. He sees a bunch of animals in cages, among them a monkey and, as we're watching, we think how odd it is to see a monkey in such a small cage and how cruel it seems to confine the creature in such a small space. But the information doesn't seem important to the plot so we don't really dwell on it until later when Takabe's exploring Mamiya's apartment and in the bathroom he finds a dead monkey tied ritualistically to a shower pipe. Are the two monkeys related somehow? We automatically think about it, but we can't think of anything conclusive based on the information. Then, driving home, Takabe suddenly has a compulsion to run into his house, where has a hallucination about his wife triggered by the monkeys. We can't see precisely how the monkeys relate, but we sense a thematic connexion maybe. It's the inability to define why the things are connected that enhances the effect. Takabe's wife has a debilitating mental problem, maybe we can see her as caged and evoking the pity Takabe must have instinctively felt for the monkeys.

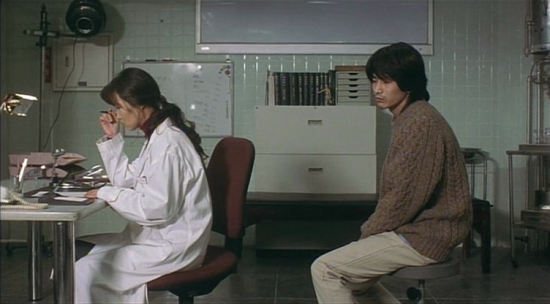

A few reviews inexplicably refer to Takabe as being immune to Mamiya's technique, though the scene I mentioned above shows this clearly not to be true. There's a scene where Mamiya is interrogated by Takabe and he tries to use his technique on him, but is impressed when Takabe thwarts him by taking control of the message--Mamiya tries to present a narrative about how trying it is taking care of a wife with mental problems, talks about how Takabe keeps his professional and personal life separate, but Takabe takes over, altering the narrative so that criminals like Mamiya are the reason he can't devote his full attention to his wife. Now if Mamiya persists, he can only possibly manipulate Takabe into killing Mamiya.

So this is an effective film about the power of memes. The climax of the story, the showdown between Takabe and Mamiya, is incredibly satisfying, though it's followed by another scene that somewhat disappointingly modifies the whole story and Takabe's character. Without its last few minutes, I'd say this was a very good film.

No comments:

Post a Comment