How's this for a synopsis: On the brink of World War I, the young girl who would grow up to be the famous poet Oda Schaefer goes to live with her insane surgeon father who's obsessed with dissecting cadavers of foetuses and anarchists to find the root of evil. Young Oda finds an injured Estonian anarchist author and soldier and hides him in the attic of her father's laboratory. She performs surgery on him and nurses him back to health, learning much about life, love, and writing along the way. And yet all the Wikipedia entry says for 2010's Poll (released as The Poll Diaries in the U.S.) is "The Poll Diaries is the most expensive film that has ever been made in Estonia." That may be, but it's certainly also worth mentioning that the film is an impressive, romantic melodrama.

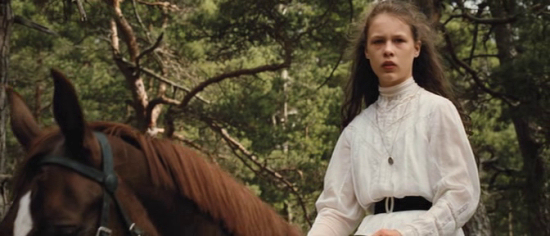

Supposedly this is based a true story from Oda Schaefer's youth, though Wikipedia's biography for her names her father as "Eberhard Kraus, one of the early Baltic writers and journalist," not the proto-Mengele named Ebbo von Siering we see in the film. It's not so much the luridness of the character that leads me to doubt the veracity of the portrayal as much as the fact that he's one of so many thematic elements put together in one spot. He forms part of the tapestry of melodrama that illustrates the formation of young Oda von Siering's (Paula Beer) personality.

The real life poet, Oda Schaefer, apparently a great aunt of Poll's director Chris Kraus, was part of an anti-Nazi community of writers and artists in Germany, so having someone rather like a Nazi in her life illustrates this aspect of her developing personality.

The movie reminds me very strongly of Spirit of the Beehive, which also features a very controlling, scientist father contrasted with his imaginative daughter who secretly shelters an injured rebel soldier. The girl's fixation on Frankenstein's monster in that film is recalled in Oda's desire, at the beginning of this film, to learn from her father. As the film opens, she arrives at his home having travelled in a wagon with the corpse of her mother (whom Ebbo had divorced) packed in ice.

She's also carrying the preserved foetuses of Siamese twins as a gift for her father.

These are rather appalling to her stepmother, Milla, an aristocrat whose dwindling family fortune is reflected in the strange, crumbling seaside mansion in and around which the whole movie takes place.

It also works as a visual metaphor for Ebbo as the thing looks rather like a dissected corpse. The impression is that Ebbo, who was kicked out of university for his theories on eugenics, married Milla for her money and social position. The two seem to represent two forms of aristocracy, one old and one new, both presuming a right to handle the lower classes as they see fit.

Because he's an underdog--having lost his professorship--and the person Oda feels closest to, the movie actually begins with its sympathy attached to Ebbo and against Milla, who callously tosses the foetuses into the sea. Milla's son Paul secretly helps Oda recover the specimen and the two stash it in a barrel of schnapps which, as you might imagine, pays off in a rather critical accident later in the film.

Schnapps ends up being the name the Estonian rebel asks Oda to call him, not wishing to reveal his real name, possibly because, he hints, he is a famous anarchist writer. Unlike the soldier in Spirit of the Beehive, who the girl is attracted to as she associates him with a monster, the soldier here is quite handsome and Oda develops a crush bound up with her own desire to become a writer.

Both Schnapps and Oda's father exhibit a misogyny in dealing with her, one telling her she needs to be more like a man if she wants to be a decent writer, the other telling her she needs to be more like a man if she wants to be a decent doctor. Schnapps makes a good point, though, when he tells her a good writer must be "like a wolf", must see things through, and contemptuously points out to her that she has a tendency to leave off things she feels passionate about when she's half done--he tells her he's able to hold his breath underwater a long time because he has a slow heartbeat so she demands to count his pulse but becomes distracted by something else halfway through.

In a charming scene, he dresses her as Napoleon and himself as Josephine. The two dance before he instructs her to begin writing only if she imagines she's Napoleon.

It's not strange a soldier of an ideology would have this point of view on adhering to one's purpose. Though this somewhat positive view of a trait linked to masculinity is mirrored by Ebbo's desire to see and impose order on the world. The film's sympathies completely shift to Milla after Ebbo assaults her as part of an assertion of control. We see why this supposedly masculine attitude can be horrible and what the film portrays as a feminine attitude, a capacity to adapt to change, can be a positive thing.

The film has a very modern, sort of academic beauty to it and the story, despite comparing unfavourably to the subtler and stranger Spirit of the Beehive, is a very enjoyable, layered romance.

No comments:

Post a Comment