In love and relationships, passions run so high and people have so much pride on the line, each party in a dispute may be fully committed to a different version of reality. Many comedies and dramas have been written from this premise, including the charming 1957 musical Les Girls. Featuring songs by Cole Porter that don't rank among his best they're adequate for the film because lovely visuals and a great cast more than pick up the slack. The screenplay isn't Rashomon but it's not bad, either, and director George Cukor exercises his formidable storytelling instincts.

The man with the sandwich board wanders a crowded street outside a courtroom in which the sensational trial everyone's talking about forms the film's framing story. A wealthy society woman named Sybil (Kay Kendall) has written a scandalous memoir and she's been taken to court for it by Angele (Taina Elg), with whom Sybil once worked as a dancer on stage in Paris. The film's divided into three parts for three versions of events and in the first one Sybil tells us about Angele's torrid affair with their manager and co-star, Barry Nichols (Gene Kelly).

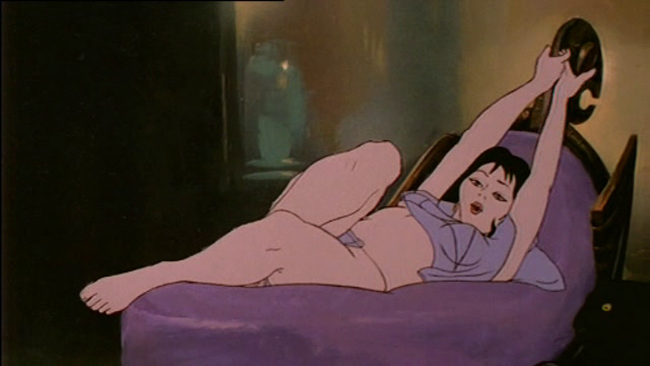

This was my favourite part of the movie as we're introduced to the three flatmates who banter engagingly about life in Paris and devotion to work. In this, Sybil's version of events, Sybil is a composed, sensible woman; Angele is reckless and romantic; and rounding out the trio is the ever chipper but somehow unobtrusive Joy (Mitzi Gaynor). Despite their misgivings, Sybil and Joy help conceal Angele's affair with Barry even when they're not supposed to know about it themselves. Angele and Barry go through a thin pantomime of greeting each other for the neighbours' benefit and then take off together in a car around the corner.

This sequence has the best song, "Ca C'est L'amour", in a really lovely scene where Angele and Barry relax in a row boat.

Angele's fiance is incensed by Sybil's account so Angele takes the stand to tell the story of an extravagantly alcoholic Sybil torn between Barry and a wealthy Englishman--Sybil's present day husband. Finally, Barry himself takes the stand to set things straight--it was Joy he'd been going with the whole time. But as Joy herself remarks, there's too much in Sybil and Angele's stories they couldn't have made up so by the end of the film there's a reasonable argument for the veracity of any one of the stories.

Supposedly the alternate points of view are motivated by Sybil and Angele each believing that the other had tried to commit suicide over the impossibility of being with Barry. Barry's story offers an explanation for the confusion but really doesn't clear things up.

There's a terrific dance sequence at the end seemingly modelled on The Wild One--minus the emotionally authentic portrayal of misfit youth but with a great heat of its own. It follows a tradition in musicals of the 50s and late 40s wherein there's at least one big dance sequence that has nothing at all to do with the plot. The movie resolves on a nicely uncertain note, allowing the audience to contemplate the insoluble puzzle of tangled romance.